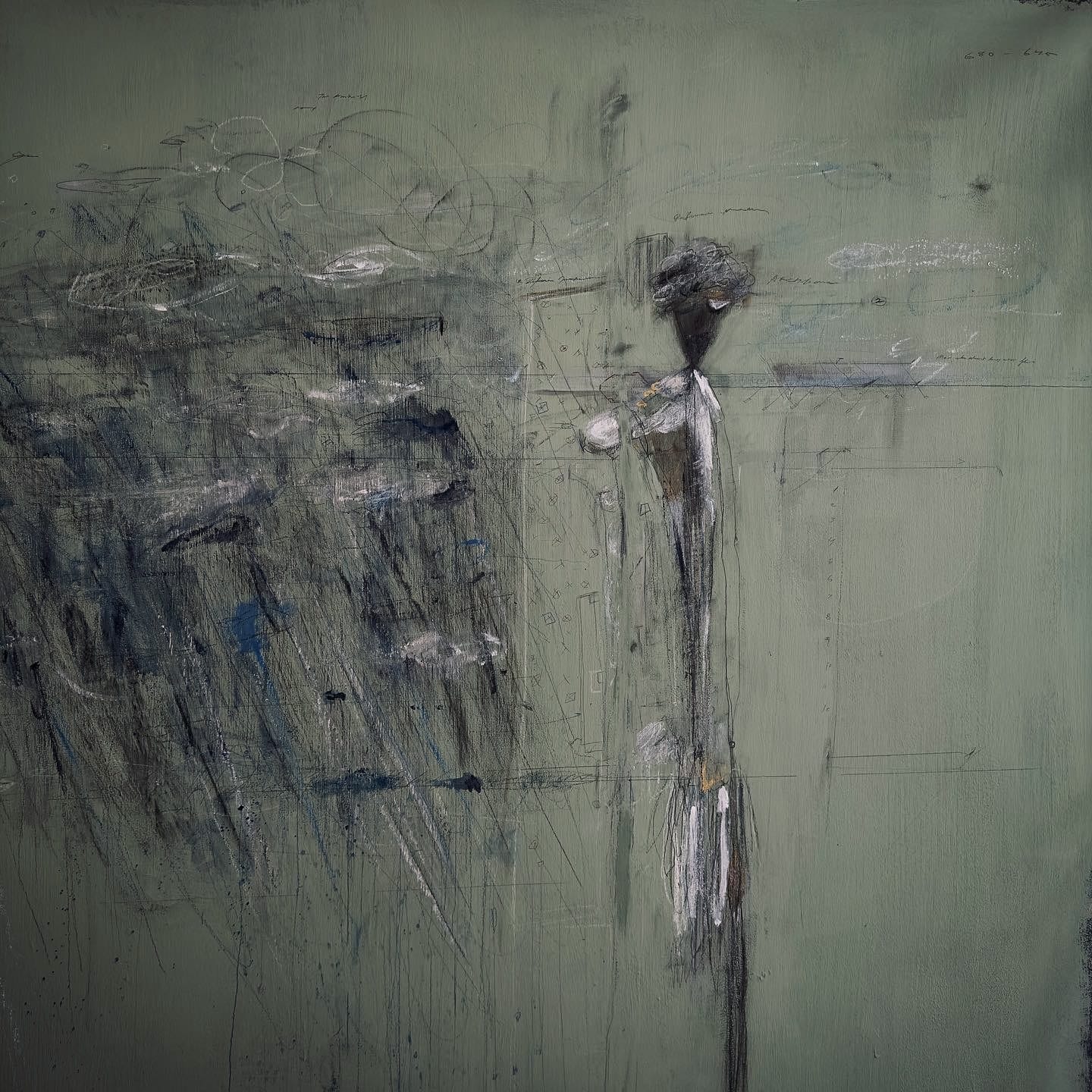

Born in 1998, residing and working between Brooklyn and Berlin, Jet Le Parti is an American multidisciplinary artist working in painting, poetry, and sound. He is best known for his introspective poetry and gritty paintings, exploring notions of alienation, isolation, and cultural contradictions. The artist has been working in an underground gallery and studio project titled Base 36, where he has been preparing for his first show at an underground gallery Relaispunkt.1. On the occasion of the show titled Post-Script: Field Notes, we are pleased to have a chat with the artist, discussing his youth, influences, paintings, and other creative endeavors.

Sylvia Walker: Dear Jet Le Parti, could you please introduce yourself in a few sentences to our readers who might not have heard of you—yet?

Jet Le Parti: Hello Sylvia—thank you for having me. My name is Jet Le Parti. I am a painter, poet, and sound artist, currently living and working throughout the United States and Europe. My work explores a variety of themes, typically within philosophical or conceptual contexts. I look forward to providing more context throughout our conversation.

SW: You grew up in a military family in the South of the United States before finding your artistic awakening during your studies and travel abroad. In what ways do we encounter personal experiences in your works?

JLP: My personal experiences are unavoidably interwoven throughout my work. Recently, my reflections on my external identity have become more pronounced, a contrast to earlier phases of my practice, which engaged more directly with universal themes. Initially, my work leaned towards abstract concepts such as time, space, and the unconscious, as my immediate personal experiences were deeply entwined with these metaphysical topics. It was only after achieving a sense of closure from my introspective journey that I began to confront the implications of my experiences in the external world. This transition has led to deeper engagements with critical theory and a reevaluation of my history, identity, morality, and values within contemporary contexts.

Growing up in the South, I was always in proximity to a wide range of societal issues—racism, misogyny, homophobia, xenophobia, violence, and so on. I’ve come to understand that these issues are not confined to one region but are pervasive globally, including within institutions in what is considered the progressive North and West of the U.S. and other first-world hubs throughout Europe. Despite this evolution, I maintain a degree of detachment from directly addressing themes of race and ethnicity within my work, as I aim to be cautious about my experiences as a person of color being misinterpreted as a commodity or reducing my identity to simplistic narratives within neoliberal contexts.

SW: In the introduction for this interview, your artistry is described as multidisciplinary. However, it seems as if poetry and sound are not necessarily part of your main artistic practice, co-existing next to your painterly practice. Or do you aim to include sound, music, and poetry in your exhibitions as a visual artist?

JLP: Poetry, verse, and sound are all intricately intertwined with my primary practice; they are central to it. For instance, the body of the Melting Blue works began as a sound process, and recent Postscript pieces all stemmed from deeper exploration into poetry and literary classics. I just haven’t been as open to sharing this work on a standalone basis thus far because it doesn’t seem fitting within the context of streaming platforms and social media, especially given their experimental nature. Nevertheless, fragments of my work are evident throughout the canvases, particularly in recent pieces.

The association of loose imagery, metaphors, and allusions found in poetry parallels well with my approach to painting. It feels as though the same brain associations are in dialogue. In that sense, it’s fluid to incorporate one into the other while also being able to segregate the two as needed. Music and sound, on the other hand, represent the antithesis of this approach. As mediums, their amplified, resonating, provisional, and experiential qualities offer a type of medium that reaches the emotional point immediately. With this in mind, my approach is far different, but the end goal of capturing the essence or attempting to “find the words” remains the same.

Regarding exhibitions, I’ve always been open to showcasing different mediums together while also being open to isolating them when contextually appropriate. The difficulty lies not in the work itself but rather in the broader environment it exists within. In major cities, where people primarily know your work and character through brief, contextless moments, it can be challenging to coherently highlight the setting and meaning of what you sought to convey within a single-night opening or a few-week exhibition. I’m still contemplating the best way to present these practices without reducing or shifting the intended purpose of the work. This upcoming exhibition will be an experiment in this regard.

SW: Sounds exciting and interesting. How would you describe your painterly practice? What is your purpose, methodology, and process in painting?

JLP: My approach is relatively research and reference-based. I work with ideas within various disciplines and incorporate experiences as I am exposed to different ideologies and environments. This method allows me to challenge perspectives and enrich my understanding of the subjects I explore in my paintings. It involves discovering a variety of aims, angles, and avenues to dissect and, at times, outright escape the paradoxical and challenging reality of this venture. Consequently, my painting process follows suit through careful consideration of selecting the most appropriate medium for communicating whatever theme is intended.

When I started painting, my purpose was simply to communicate an experience and connect with an imagined viewer—someone who could, in some way, relate and feel that they are not necessarily alone. Over time, this purpose has shifted towards a more internal reflection, fostering a deeper understanding and engagement with my experiences and insights. With this shift, I’ve become content with the idea of possibly only communicating with myself.

SW: There are some clear similarities between you and, of course, Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988)—it is even one of the first things people notice and point out. Let’s address this elephant in the room first. What is your response to these similarities between you, your work, and Basquiat’s?

JLP: My life, work, and character are not remotely similar to Jean-Michel Basquiat’s, except for being broadly categorized as “black artists.” I encourage those who make these comparisons to reflect on the reasons behind their observations. I typically avoid categorizing people, especially with terms like “black,” as they often result from an oversimplification of diverse experiences under a circumstantial umbrella shaped by external oppressive conditions. However, in cases such as those where our identities are quickly compared and “one of the first things people see,” emphasizing this distinction amongst others may be necessary.

Our backgrounds are vastly different. Basquiat was of Puerto Rican-Haitian descent and grew up immersed in New York City’s art scene, whereas I am an African-American with German roots, having spent most of my life in the South, largely indifferent to the arts. When it comes to our subject matter, the contrasts are extensive. My work does not primarily engage with social commentary or pop culture references, nor has it been conceptualized around my race or perceived gender. Our life experiences and social interests further underscore our differences. I do not see myself as a pop icon, or a generational symbol, nor do I possess any format of celebrity status—nor do I aspire to. I have no involvement with New York’s art scenes or gallery circuits, nor have I worked in locations financed by gallerists’ capital and institutional philanthropy. I have always found the idea of selling my work, let alone marketing myself, repugnant, albeit necessary. I am not part of any creative circles, movements, bands, brands, or emerging artistic connections. On the contrary, I have maintained complete independence throughout my career, working in relative isolation. However, people with superficial interpretations and insincere interests will always see what they wish to see.

Considering we are in an era where Basquiat’s legacy is hyper-commercialized through extensive collaborations across various popular culture channels, there’s been an emergence of mass cultural awareness surrounding his persona. Given that most interactions with my work occur through social media and digital platforms, this awareness indirectly intersects with my (and other black artists’) practice, making the widespread media coverage a contributing factor to the overlapping perceptions(of our identities. This situation is further manifested across highly engaged markets, from luxury jewelry to fast fashion, alcoholic beverages, and novelty items, leading individuals, often with minimal art knowledge and/or purely commercial interests, to become exceedingly aware of his iconography. Moreover, major institutions leverage curatorial strategies to capitalize on contemporary race and social justice movements in superficial manners. These strategies are often backed by identity entrepreneurs who, while portrayed as champions of the black experience, tend to be opportunists exploiting these narratives for personal gain, showing a disregard for the broader implications of their actions in the greater context of their kind.

As a result, these efforts superficially honor Basquiat and other black artists, creating a simplified and highly decontextualized narrative of black artistry projected as the new cultural standard. This template is imposed on anyone fitting a similar aesthetic profile, in this case, the bare requirements being black and painting, thereby contributing to the overlapping perceptions influenced by the media’s portrayal. Therefore, when I appear online and encounter such generalized and uninformed viewpoints, it is both anticipated and inevitable. That being said, I hope this answer has provided further clarity for future reference.

SW: An answer clearing the air once and for all; thank you very much. Yet, in your earlier work there were some typical Basquiat-esque elements when it comes to the doodled figures and writings. However, it seems as if your work has transitioned into a more personal, and minimal visual language—marked by scribbles, writings, Twombly-esque marks, and intriguing details. Could you please expand on this transition?

JLP: It’s crucial to acknowledge that before I began painting roughly seven years ago, I had no exposure to or interest in the visual arts, art history, or any traditional or contemporary notions of what it means to be an “artist.” Being entirely self-taught, I hope it’s understood that my initial work, while perhaps perceived as raw, served as my starting point and not as a definitive reflection of my overall quality or stylistic consistency. In essence, my early work looked the way it did because I was learning the fundamentals of painting.

My artistic journey was sparked by a pressing need to address something deeply personal. This dedication led me to explore and reinvent styles from one work to the next, with each piece representing a fresh exploration of ideas through different visual vernaculars and themes. My personal growth and expanding grasp of art traditions have advanced in lockstep with these stylistic evolutions. Should you have the chance to view my work up close, you likely would discover the myriad nuances, themes, illusions, ideas, and references within the paintings that are often overlooked or generalized in digital viewings.

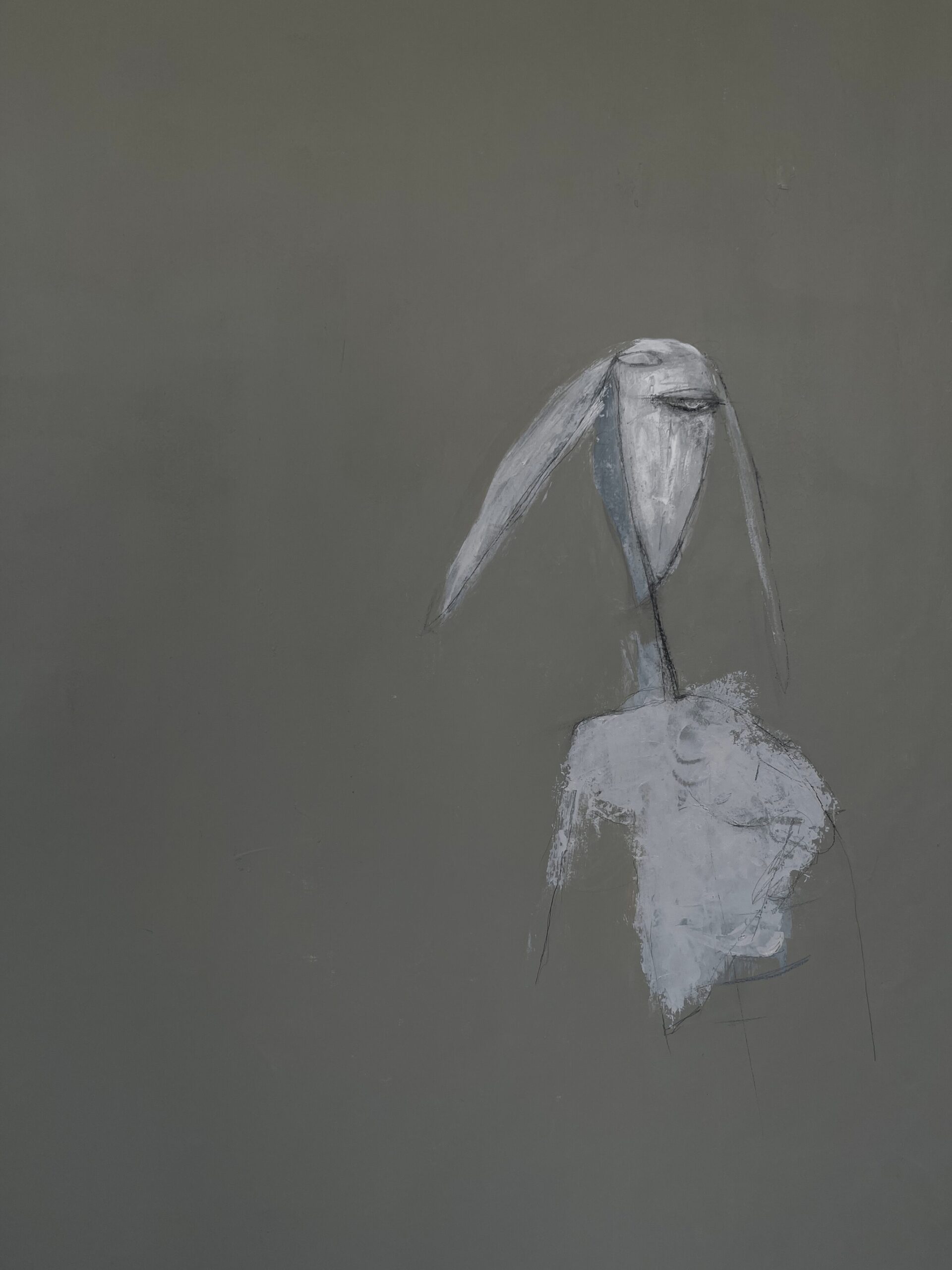

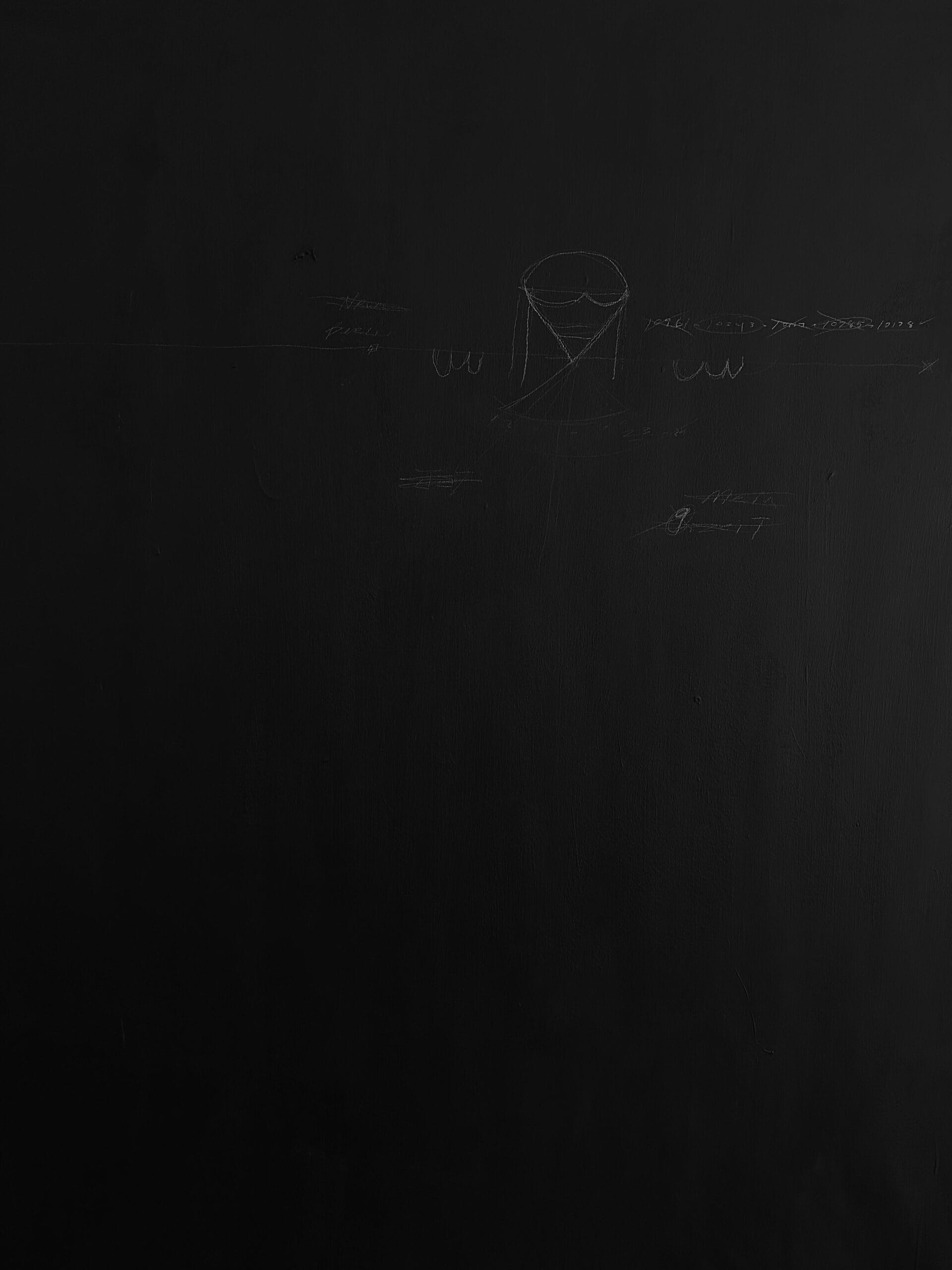

As for my recent works, as previously stated, I am perpetually evolving. My relationship with both painting and life has seen profound changes through my dedicated work with the medium, personal development, and external challenges I’ve faced. The transition toward a more minimalistic and weathered approach stems from fatigue through this consistent confrontation. This method is rooted in an existential methodology, prioritizing the notations and remnants of an individual’s attempt to explore their experience stripped of comforting presuppositions rather than approaching the canvas with the expressive vibrance of an optimist’s imagination.

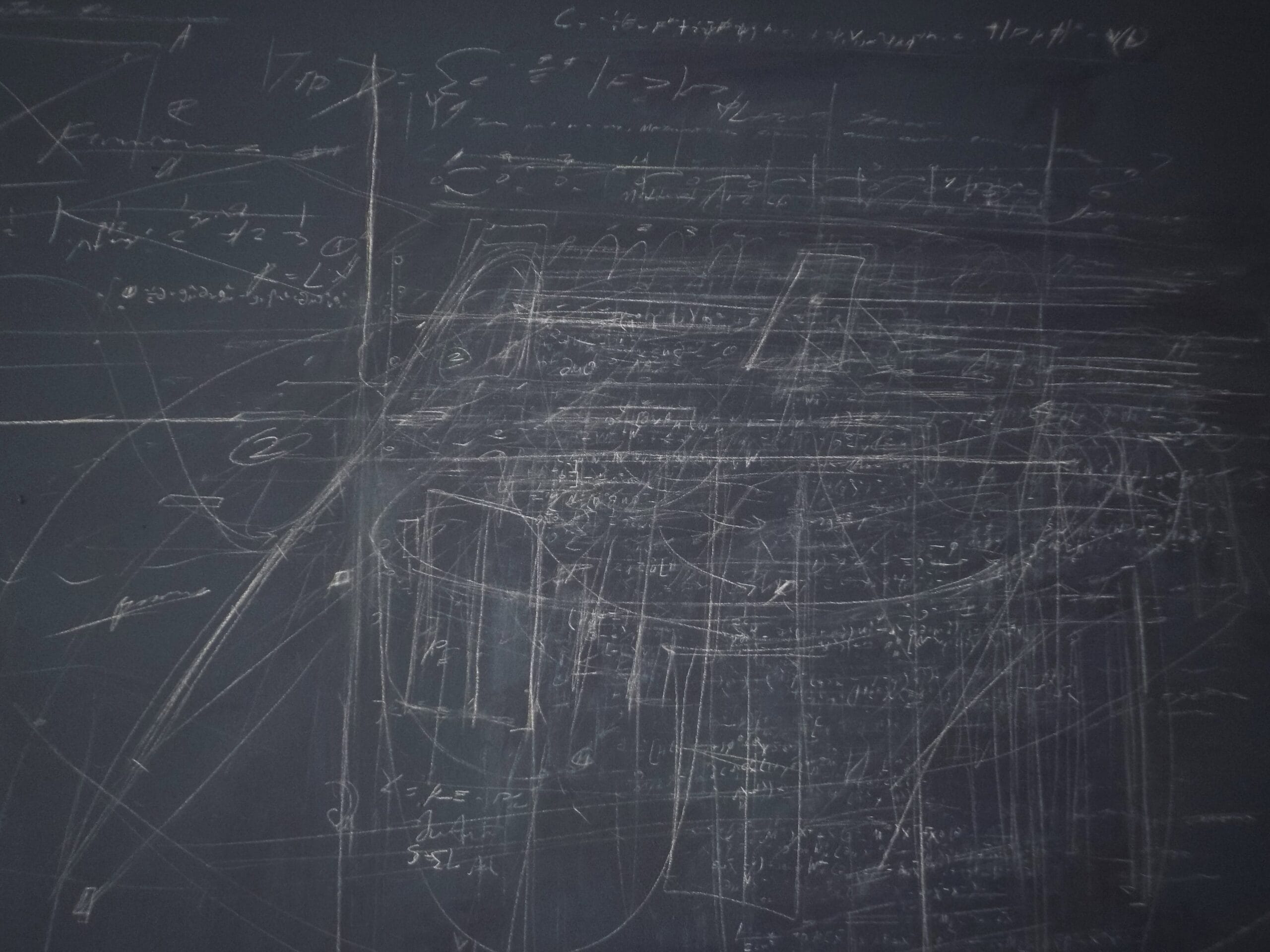

SW: For the past few years, you have been working in a large warehouse that seems to match the grittiness of your art—arguably a match made in heaven. What is Base 36? Who is behind it? And what can we expect in the future?:

JLP: Base 36, alongside Relaispunkt and other collaborative projects my colleagues and I engage with, began as a research-based initiative by a group of like-minded individuals passionate about the arts, history, cultural criticism, philosophy, and contemporary phenomena. This collective, primarily composed of artists, evolved to establish gallery-like spaces that present work in a critically conscious manner without compromising the authenticity of expression due to commercial pressures, censorship, or limited resources. Our pursuit of authentic expression beyond the constraints of contemporary art scenes and culture is embodied in our project.

Personally, the warehouse is where I started. From my days as a teenager exploring deserted brickyards outside Columbus, Georgia, to initiating my practice while attending university in Philadelphia and delving into underground scenes in South Philly, Strawberry Mansion, and Kensington, I’ve significantly matured within the context of these abandoned environments. It was not until relocating to Brooklyn that these vacant-like spaces would become a place I call home.

Base 36 later emerged as a by-product of my interactions within Brooklyn’s underground rave and after-party scenes, where my illegally inhabited studios were transformed into makeshift venues on weekends. This routine, blending long days of painting in vacant, complete solitude with weekends filled with the stimulated bodies of substance-filled strangers and inescapably loud drum loops and sounds, created a polarizing experience. The juxtaposition of raw, hyper-progressive, and immediate rock-bottom cultures against a day-to-day academically driven environment was dizzying but eye-opening. Despite the physical and mental challenges, this lifestyle was invaluable for cultural awareness and growth, providing opportunities to interact closely with individuals from radically varying backgrounds who found solace within these spaces.

The transition to formal art exhibitions arose from the desire to showcase our work and that of artists we believed in amidst restrictive and misaligned local options. Using proceeds from prior events, we acquired a new warehouse to independently run our gallery project, relying on a small but dedicated team. Our experience in the DIY environment equipped us with the necessary skills for curation, installation, logistics, and more, allowing our collective to adeptly manage exhibition demands. Four years into this venture, Base 36 has evolved into a more decentralized structure, embracing diverse mediums like music, sound, literature, and film. Initiatives such as a joint residency program with Relaispunkt.1, a rolling-basis grant program, and annual exhibitions have expanded our support for artists aligned with our mission, fostering greater independence and passionate expression.

At our core, we remain a research group interested in taking action within the world. While we align with contemporary art environment aesthetics, our defining feature remains fluid. We’ve found significant value in conversation and discourse through the art tradition, applying new perspectives to our interests. However, we’re prepared to comfortably transition this project as needed, exploring private interest mission sets in other mediums and media as seen fit.

SW: Technically and visually, the aforementioned transition is apparent. You incorporate techniques of layering and nihilist ciphers, using materials ranging from house paint to graphite. Do you believe you have found your personal technical formula?

JLP: Aesthetically, I feel I’ve found a visual environment and style that truly aligns with my current perspective. This past year, I was deeply immersed in the literary works of German, Russian, and French thinkers while living in Germany, surrounded by items looted by Germans with origins from all around the ancient world. The geopolitical dynamics of Russia and the European Union loomed in the background, accompanied by a pervasive feeling of annihilation anxiety, all experienced as an isolated foreigner with blood ties to the nation I resided in.

This period has profoundly shifted my perspectives on globalization, geopolitics, the media’s portrayal of world events, and the ownership of history, among other themes. Characterized by a rapid sequence of relocating from one home to another, from bed to bed, state to state, I’ve been constrained by visa limits, financial challenges, and commitments, which have prevented me from settling comfortably anywhere. Utilizing materials that are immediately accessible in any environment, such as ink, house paint, and graphite, has helped me stay present and engage with the transient nature of existence while also affording me the freedom to continue moving and expressing myself as necessary. These materials, always within reach, enable me to create regardless of the setting I find myself in, be it hotels, bedrooms, or short-term rentals. While I continue to work with oils and explore realism and other styles out of curiosity, my current style adequately reflects my present state and is likely the path I will continue on as I navigate my itinerant lifestyle.

SW: What societal critiques or philosophical notions recur throughout the selected works for this show?

JLP: The show isn’t directly centered around social discourse in a contemporary sense but rather offers a reflective examination of modernity and the progression of history at large. After taking a break from Melting Blues, I shifted away from attempting to directly express social commentary intertwined with broader societal themes such as hyperreality, the economy of the signs, the spectacle, and so on, especially in the context of visual arts and its surrounding culture. Conceptually speaking, this body of work has become more introspective, existentially motivated, and overall more emotionally driven. The medium selection of nihilist ciphers and abstracted classic imagery made through industrially produced materials resonate well with this aesthetic essence.

That’s not to imply the absence of commentary within the work; it certainly exists, but it emerges from an individual perspective grappling and moving through these abstractions rather than trying to encapsulate broader concepts into fixed and refined structures. It’s also not a body of work fixated on a metaphysical or otherworldly interpretation of reality as well, resting from a starting place of nihilism and working up from there. These aspects are organically integrated into the reactions the works tonally aim to elicit without the need to underscore external points that are already evident. In other words, these works are reactions, reflections, notations, ideas, and footnotes provided from an inquiring viewer’s perspective rather than a prescriptive commentary on the way things are or ought to be.

SW: To conclude, what’s next?

JLP: As of now, I am in the process of finishing up a body of sound work and a small collection of written work as well. After completing them, I’ll likely take a step back from the outward-facing aspects of our initiatives and instead focus on supporting the development of projects for the next wave of artists. Nonetheless, I will continue my personal work and anticipate returning to exhibitions when it feels appropriate. Fortunately, there are incredibly talented artists and thinkers set to engage with our spaces shortly, ensuring that these projects will be in capable hands.

Last Updated on February 16, 2024