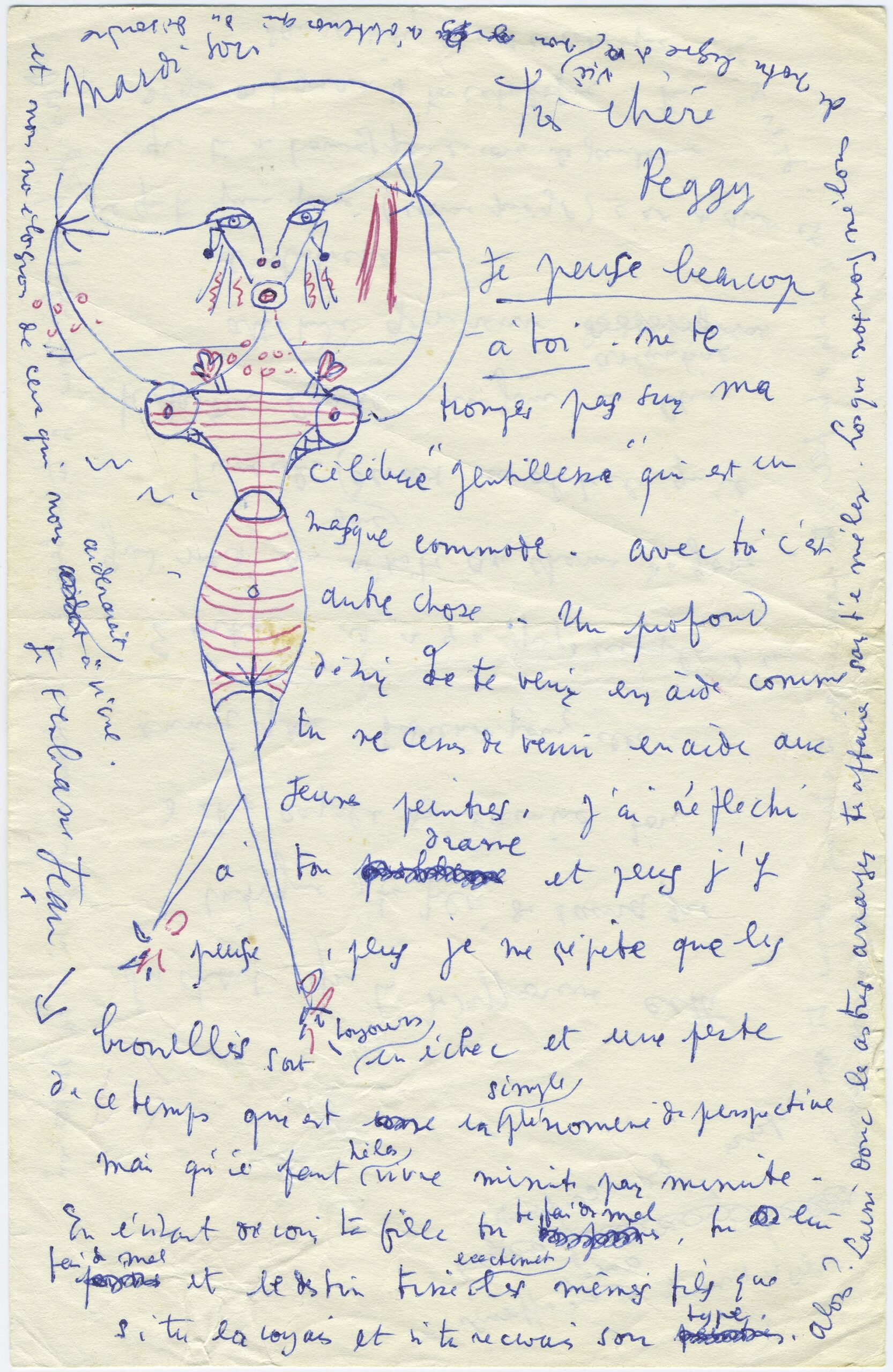

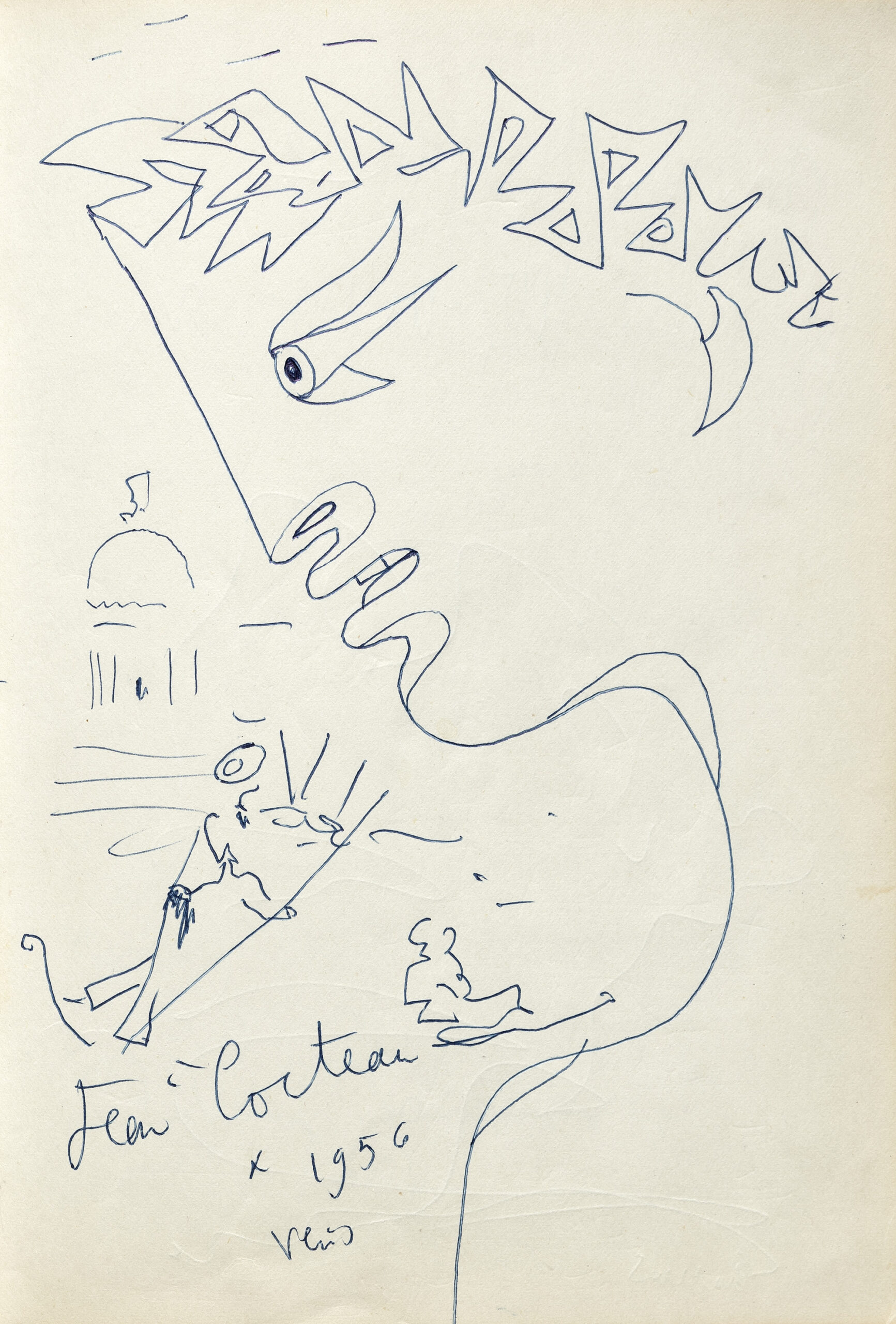

Born in 1993, residing and working between Los Angeles and Paris, Chloë Cassens is an American writer and a representative of the Severin Wunderman Collection, the largest collection of works by French artist Jean Cocteau. Cassens’ trajectory is deeply intertwined with Cocteau’s work, guided by a familial connection as Wunderman’s granddaughter. On the occasion of the launch of her new project “SACRED MONSTER” (a biweekly essay centered around Cocteau, his friends and contemporary culture) as well as the exhibition Jean Cocteau: The Juggler’s Revenge currently on view at the Peggy Guggenheim in Venice, Italy, we have the privilege of chatting with the writer, discussing her influences, her goals, the impact of Cocteau’s work on culture, and much more.

Jonathan Bergström: Dear Chloë Cassens, we are thrilled to have this conversation with you. First of all, could you start by telling us about your new project, SACRED MONSTER?

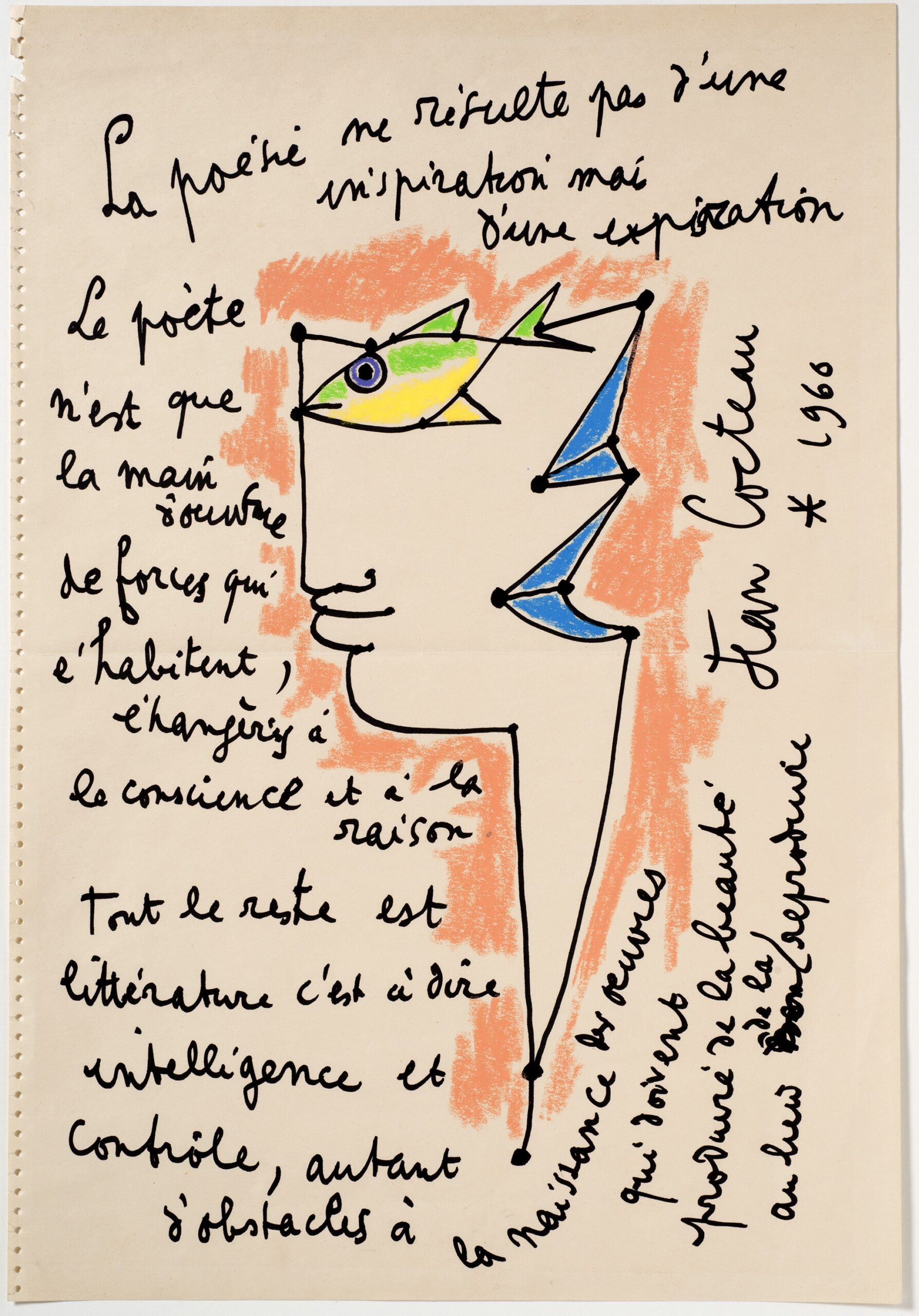

Chloë Cassens: Thank you for having me. SACRED MONSTER is a project I’ve launched that celebrates and educates the world about Jean Cocteau and the Severin Wunderman Collection. Presently, it’s taken the form of biweekly written deep dives, available on a subscription-based model. I have many other projects coming up in the future, though. This is just the beginning!

JB: What, in your opinion, are the distinguishing factors that make Jean Cocteau so unique?

CC: Like many pioneers, Jean Cocteau was not truly accepted or celebrated in his lifetime, even though today, 60 years after his death, so much of his work is still incredibly prescient, fresh, and relevant. I believe that a lot of this is due to the fact that he was very vulnerable and human in his work, which is not easy.

JB: In modern culture, where do you perceive Cocteau’s influence to be the most prevalent?

CC: This is a difficult question to answer, because I could go on about this for hours. For example, I see his influence everywhere, from the way that modern celebrities are encouraged to behave in public and create their image, to more concrete examples, such as Disney drawing much of their inspiration for their version of Beauty and the Beast from Cocteau’s original vision of the fairy tale.

JB: Among Cocteau’s various artistic expressions, which aspect strikes the deepest chord within you? Is it his poetry, filmmaking, visual art, writing, or another facet?

CC: I find myself drawn to different facets of Cocteau’s work every time I engage with it; luckily, because he worked across so many mediums, there’s a lot to choose from. I am easily bored, but with Cocteau, I am never bored. I have always connected strongly to La Belle et La Bête for many reasons, one of them is that outside of Cocteau, I am a huge fan of the Flemish Masters and these paintings inspired his mise-en-scène for the film. Lately, I’ve started to revisit his writing, particularly his foray into erotica, Le Livre Blanc.

JB: Your grandfather, Severin Wunderman, and his legacy have been instrumental to this project. Could you tell us more about him and his influence on you?

CC: My grandfather was a huge force in my life and in my family’s life, a force that remains today. We were quite close, and he taught me so much directly and by observation. Perhaps the most important influence he’s had on me is the desire and responsibility to always give back to the world in whatever way that I can.

JB: How would you describe your grandfather’s relationship to Jean Cocteau and his art?

CC: Severin was obsessed with Cocteau from a young age and never met him. He started his collection at random, buying a piece he saw in a window when he was 19 years old, and continued until his death. Severin used to tell me never, ever, to purchase a piece of art with the intention of investment, that you should buy something you would be happy with and love to see in your home every day of your life.

It didn’t matter if it was something cheap you could find on the street or a multi-million dollar Picasso; as long as the intention was there, that was all that mattered. The very few times he was convinced to purchase a piece on the basis of investment, he always ended up hating and reselling it—and losing money! I think that is the reason why his collection became so significant; there was a real passion and love behind it.

JB: What do you think it was about Cocteau’s art that made your grandfather gravitate towards it?

CC: To be honest, my answer to this question changes all the time. Fundamentally, though, I think that Severin connected and saw something to Cocteau’s art that most of us still can’t see, almost like a conversation only they could hear.

JB: Could you provide further details about the Severin Wunderman Collection and its significance?

CC: The Severin Wunderman Collection is the largest collection of Cocteau in the world, and makes the entirety of the contents of the official Musée Jean Cocteau in Menton, France. It’s significant as Cocteau is the third most counterfeited artist in France, and it’s rare to have so much of one artist’s oeuvre in one place that’s accessible to the public.

JB: Jean Cocteau: The Juggler’s Revenge is currently on view at the Peggy Guggenheim in Venice, Italy, the largest exhibition of his work in the last 20 years. What does an exhibition like this tell us about his lasting influence?

CC: I think it tells us that there’s always a reverberation of his work that can be found throughout generations. Kenneth Silver’s curation is brilliant and highlights how relevant so much of his work is to our current era. I recently spoke to a group of young people at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection about the exhibition and was really moved to see their interest and curiosity around Cocteau, his life, and his work. It goes to show that, with exposure and education, his name can live on through Generation Z and beyond, past when you and I are long gone.

JB: What motivated your decision to return to your roots and represent your grandfather’s collection?

CC: There were a few factors that led to my decision to do this work, some of which I can’t discuss publicly at this time. I had a moment, mid-2022, where I realized that this was what I was meant to be doing and that truly—in the least egotistical way I can say this—I am the only person qualified and equipped to do it. It made me feel like it would be a waste of my life’s experiences with Severin, of my education, of my lifetime of growing up with Cocteau not to do this. Even though it’s quite frightening to be on my own and navigate everything as I go along, so to speak, I have never regretted making this decision.

JB: Despite living in the US for an extended period, your grandfather seemed to maintain a strong European identity. What factors contributed to this sense of European connection for him?

CC: My grandfather’s identity was certainly unique, and depending on who I speak to and where they are, it can reflect more on them than it does on him. Severin was born in Belgium and was a hidden child of the Holocaust. After the end of the war, circumstances beyond his control led him to move to the United States. At that point in time, neither country allowed for dual citizenship, and I have zero doubt that if they had, he would have possessed two passports.

But such was not the case, especially for a young Jewish person leaving Europe in this period. He returned to Belgium as a young adult (he was still a teenager) and lived there for years until he returned again to Los Angeles with my mother and uncle. From then on, he lived truly internationally, and I think that fundamentally, the most American thing about him was his passport and the fact that one of his favorite meals was an In-N-Out burger with a Coca-Cola from a glass bottle.

I do not know that I can say he spent more time in the States than he did in Europe by the end of his life. His business and offices were headquartered in Switzerland, and while he had properties in Los Angeles, London, Paris, and the Côte d’Azur, the properties he considered ‘home’ were always in France.

JB: Having also been raised between the two continents, have you ever felt a sense of belonging to one place more than the other?

CC: Absolutely. I consider myself someone who lives in an eternal gray area. I am not European enough to totally be European, not American enough to totally be American, and not Jewish enough to be totally Jewish. Instead of letting this upset me or making me feel like I don’t belong anywhere, I think it means the opposite: that I belong everywhere. Recently, I’ve started to make a second home for myself in Paris, and I share my time between here and Los Angeles. I have never connected more to the classic Josephine Baker song, “J’ai deux amours,” I consider myself incredibly lucky in this sense.

JB: Drawing from your background in podcast production and radio, in what ways have your previous experiences assisted you in navigating this project?

CC: My experiences leading to the creation of SACRED MONSTER are definitely unique. I could write an entire memoir just about my life before I turned 30. I started working when I was 14 years old at a rock club called The Roxy in Los Angeles, which led to various music industry gigs, including several years I spent as a radio DJ.

When I left music, I immediately fell into working with Liz Goldwyn at her incredible company, The Sex Ed, originally to produce its podcast and eventually moving into a role as Media Director. From all of these experiences, I’ve learned how to communicate with people and meet them where they are; I’ve also learned how to be nimble and adaptable, with the internet and social media moving at lightning speed.

JB: Do you have any specific outcomes or goals that you are striving for with SACRED MONSTER?

CC: I want people to be excited about Jean Cocteau and Severin Wunderman and to read more! I worry that today, in the era of TikTok and Reels, people aren’t sitting still and reading as much. SACRED MONSTER is, first and foremost, a written project. Old school as it may seem, I’m hoping that it’ll make people slow down and allow themselves to enjoy learning. I hope people can trust that when they subscribe, they’ll be in good hands. You are never too old or too wise to learn something new.

Last Updated on May 24, 2024