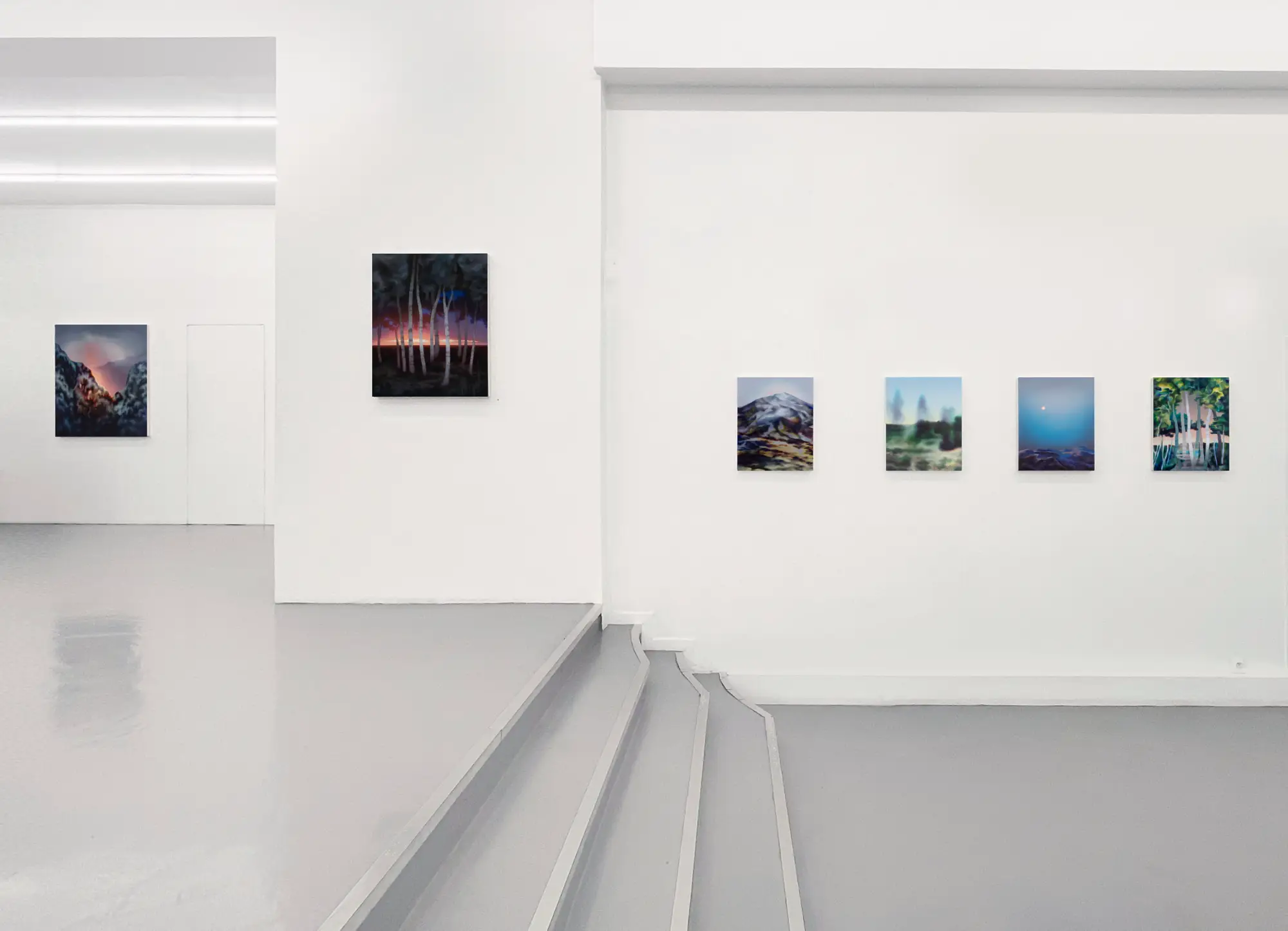

On the occasion of the duo exhibition Réminiscences with Magali Cazo at Galerie Sabine Bayasli in Paris, today we have the pleasure to sit down with an artist who has been on my radar of artists-to-follow for a while now: none other than Lena Keller. The German artist, based near Munich, is a contemporary painter working on the intersection of natural landscapes and contemporary visual culture. Blurry yet razor-sharp. Naturalistic yet artificial. A traditional genre yet contemporary poignant. Keller’s work can be described as both familiar and enigmatic, as she infuses her works with themes of yearning and estrangement, reflecting on humanity’s shifting relationship with the natural world. Her distinctive practice merges analog and digital methods, using manipulated collages of personal and found imagery as a foundation for luminous, layered compositions.

Julien Delagrange: Dear Lena, thrilled to have you. How have you been? The exhibition Réminiscences is almost coming to a close. Can you walk us through the show and share how this exhibition came to life?

Lena Keller: Hi Julien, thanks for the invite! I’m good. It’s been a busy year. I’m happy about the opportunities it has given me. The double exhibition with Magali Cazo shows landscape scenes and natural phenomena in painting. Sabine Bayasli, our joint gallerist, brought us together. Magali Cazo and I take quite diverse approaches, but we are exploring related fields and painterly means. So, from an artistic perspective, this exchange was very enriching, and I reckon that this is also noticeable for the audience to explore in the show.

JD: How did your works dialogue with Magali Cazo’s pieces in the exhibition, and what connections or contrasts did you want to emphasize? Furthermore, the exhibition title suggests a sense of recollection or echoes of the past. Could you please expand on the title and concept of the show?

LK: Our works engage with landscapes in a time when both nature and perception are in flux. Although visually, our works are linked in a kind of dissolution and blur, they differ in technique. Magali Cazo works directly with very fluid inks on paper, whereas I paint with preliminary sketches in oil on canvas. I would say you can trace some kind of disappearance and dissolution in the works. They talk about the visual experience created by an environment, like an afterimage in our head or the shift of perception. A memory that is slowly transforming and fading. The works are more references rather than accurate depictions, and the title ties in with that.

JD: How does this concept align with your approach to image-making and the manipulation of source material—which is, of course, an essential aspect of your creative process?

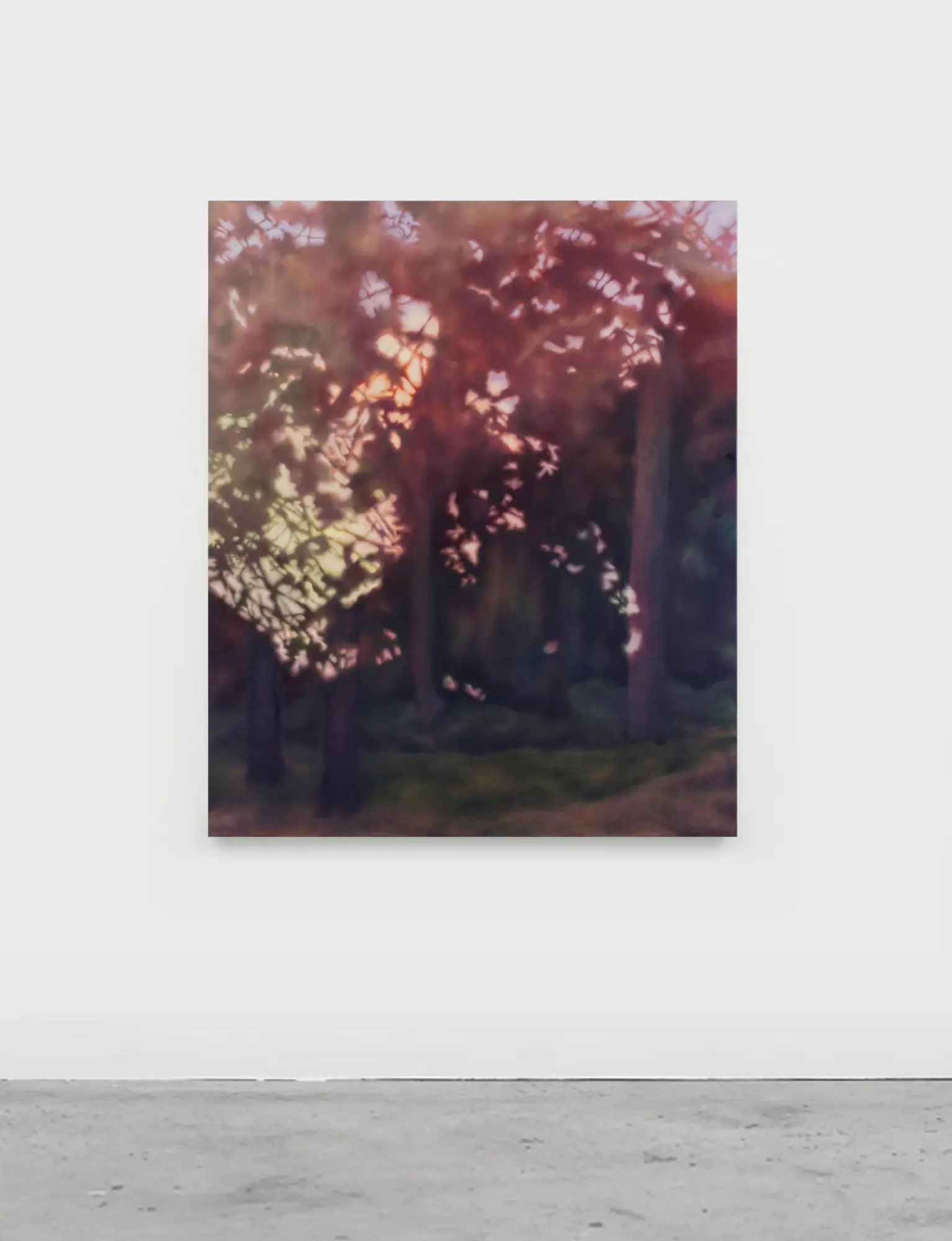

LK: My motifs aren’t depicted precisely as they appear in the real world. I am not interested in representation per se. With the emancipation from nature, man has also increasingly detached himself from it. I’m interested in this state between longing and alienation. This sense of estrangement also creeps into my pictures—or rather, I invite it in as I create constructed landscapes because I find more expressive freedom in them. For me, painting is always inextricably linked to the question of the perception of reality or the relationship between representation and abstraction, reality and illusion.

However, it is important to me that my works appear completely coherent in themselves and thus become an image. For me, my paintings are, above all, references to the visual experience of a motif. I am particularly interested in how technical images, which now permanently surround us on screens, influence or change our perception—think of filters or renderings. However, I do not regard the disturbances, restrictions, and fractures caused by shifts in perception as boundaries but as a generative factor of my time. In my work, I utilize these transformations to leave the works suspended between reality and imagination. This is also how I experience my relationship with “digital space,” which is omnipresent but difficult to grasp.

JD: Landscape painting seems to be more vital and relevant than ever, exemplified by painters such as Shara Hughes, Nicholas Party, Emma Webster, and yourself. What is your perspective on the genre in question, and why has it become so pertinent in contemporary painting in recent years?

LK: Oh, thanks for mentioning me in the same line with these giants! I’m a big admirer of Emma Webster’s and Sarah Hughes’ work, as they pushed painting so much forward in this field. I’m not sure if landscape painting is having a big revival at the moment, and I don’t give much attention to trends. Landscape painting has always changed and evolved throughout the ages and has made social changes and influences visible. Today, I find the genre is rather marginalized, not hyped. Even though—or perhaps because—we find ourselves in a time of massive ecological challenges?

I recently heard an interesting lecture by Philosopher Jan Slaby. He spoke about social affects and how society is emotionally dealing with the ecological crisis. He emphasized the concept of unfeeling, which refers to the detachment of the individual from nature. I found his observations very accurate for our times. I believe painting can make such states tangible; that is why painting is still here.

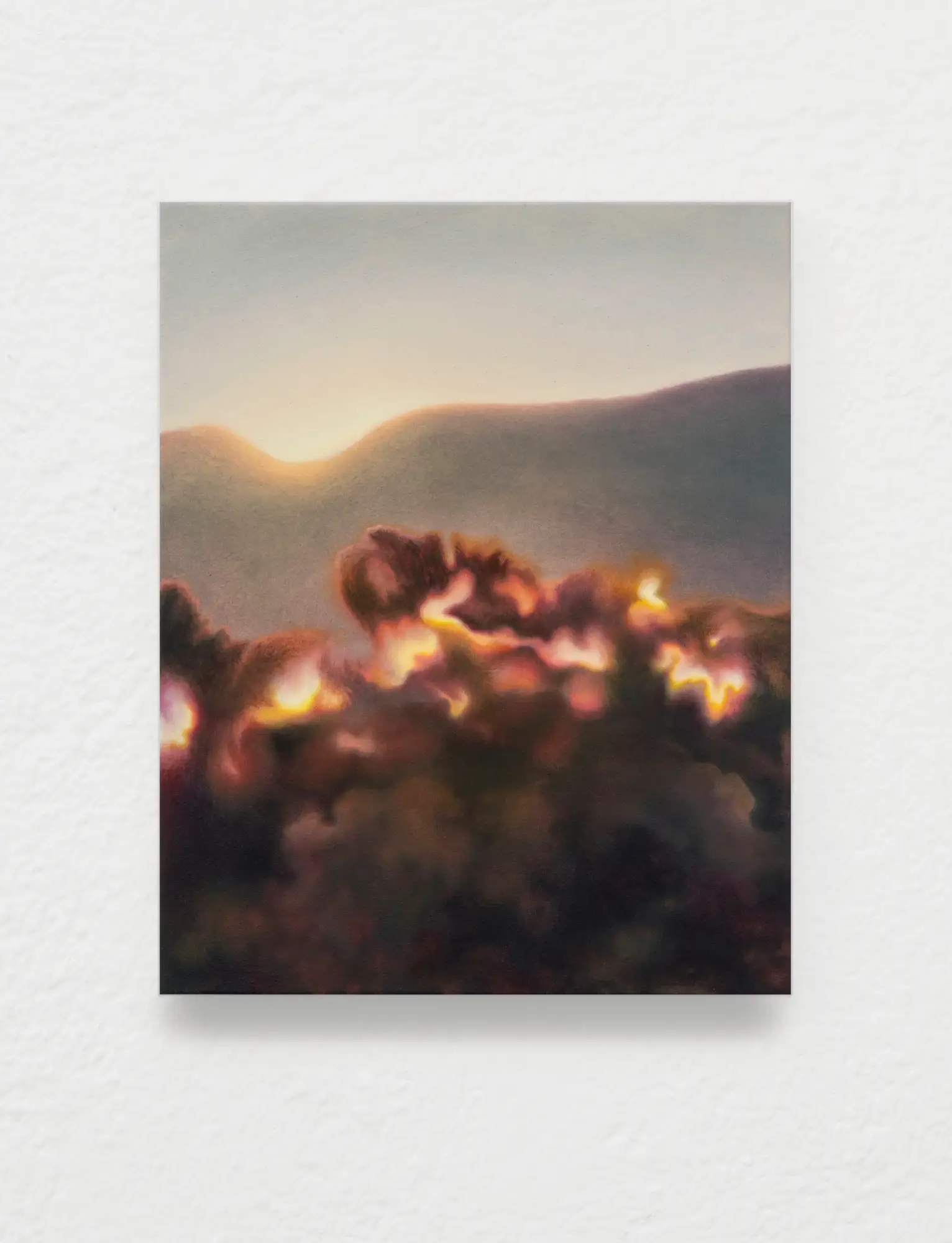

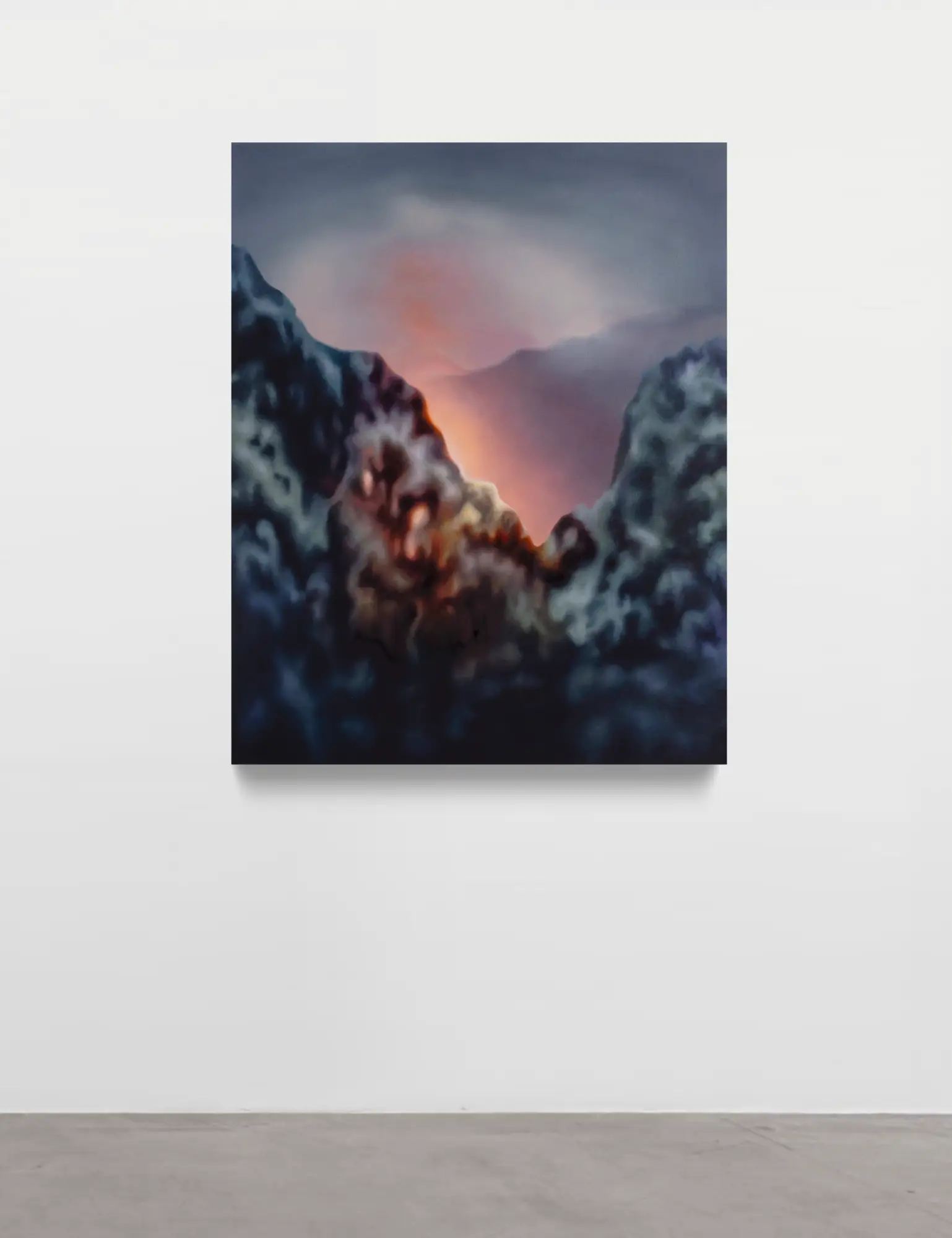

JD: A recurring motif throughout this show is the presence of fire. Sometimes, its presence is looming and silent. In other works, it is visceral and almost violent—as is the case in Dies Irae (2024) which literally translates to the day of wrath. Is the last judgment coming for us, or is it an urgent invitation for moral introspection?

LK: The title Dies Irae derives from a sequence of Mozart’s Requiem, which I found to have a strong resonance when working in the studio at that time. The sound of the composition made me think about the notion of eternal light. Not in a religious meaning but more as a concept. I interpreted this piece both as a farewell anthem in an era of ecological challenges and as a promising tribute to a constant force that underlies any form of life and matter.

This particular work is the only one in the exhibition where fire is depicted literally. In other works, it remains open whether we see a sunrise, the artificial light of a distant city, or the glow of an atomic explosion. And I am happiest when I manage to meet this “precise vagueness” in my paintings. So, light and its various manifestations are actually central to my work. I guess the new eternal light is the artificial screen illumination that permeates my paintings, for they often glow like illuminated from behind.

JD: I would argue your paintings avoid specific geographical references, creating a sense of timelessness and universality, but also of artifice or alternative worlds. Could you please expand on this subtle interplay throughout your work?

LK: Yes, that’s correct. I intentionally avoid anchoring my work to a specific place and time to convey room for both the familiar and the fictional. The line between the real and the constructed is often literally blurred in my works. Rather than separating reality from imagination, my works inhabit a space that invites reflection on what we see. I hope to offer viewers the opportunity to trace their own position in the world, which no longer consists only of tangible environments.

JD: To conclude, I would like to ask what more you aim to find in your artistic quest. What’s next for you and the landscape?

LK: Good question. For me, the beauty of working with landscape is that I find infinite creative space in it, so I don’t feel that I’m already done with it yet. When I develop new work, I usually start out with a loose, overarching idea, which develops into a clearer language over time. I need this approach to avoid getting bored with my own ideas. Also, my creative process is not purely strategic or logical. My drive comes from an interplay of the visual experience of my works and questioning what I have produced. At the moment, a new lightness is emerging visually in my paintings, but I can’t yet grasp exactly what is taking shape. Enduring this is sometimes difficult and, at the same time, the driving force. The work always comes from the work itself. For 2025, I have a few projects coming up in April and September and a larger solo show with new works at Kornfeld Galerie Berlin in October, which I’m really looking forward to.

JD: Well, so am I. Thank you for your time, and I am looking forward to more “precise vagueness” by your hand.

For more information, please consult Galerie Sabine Bayasli’s website here.

Last Updated on December 5, 2024

About the author:

- Tags: HOME