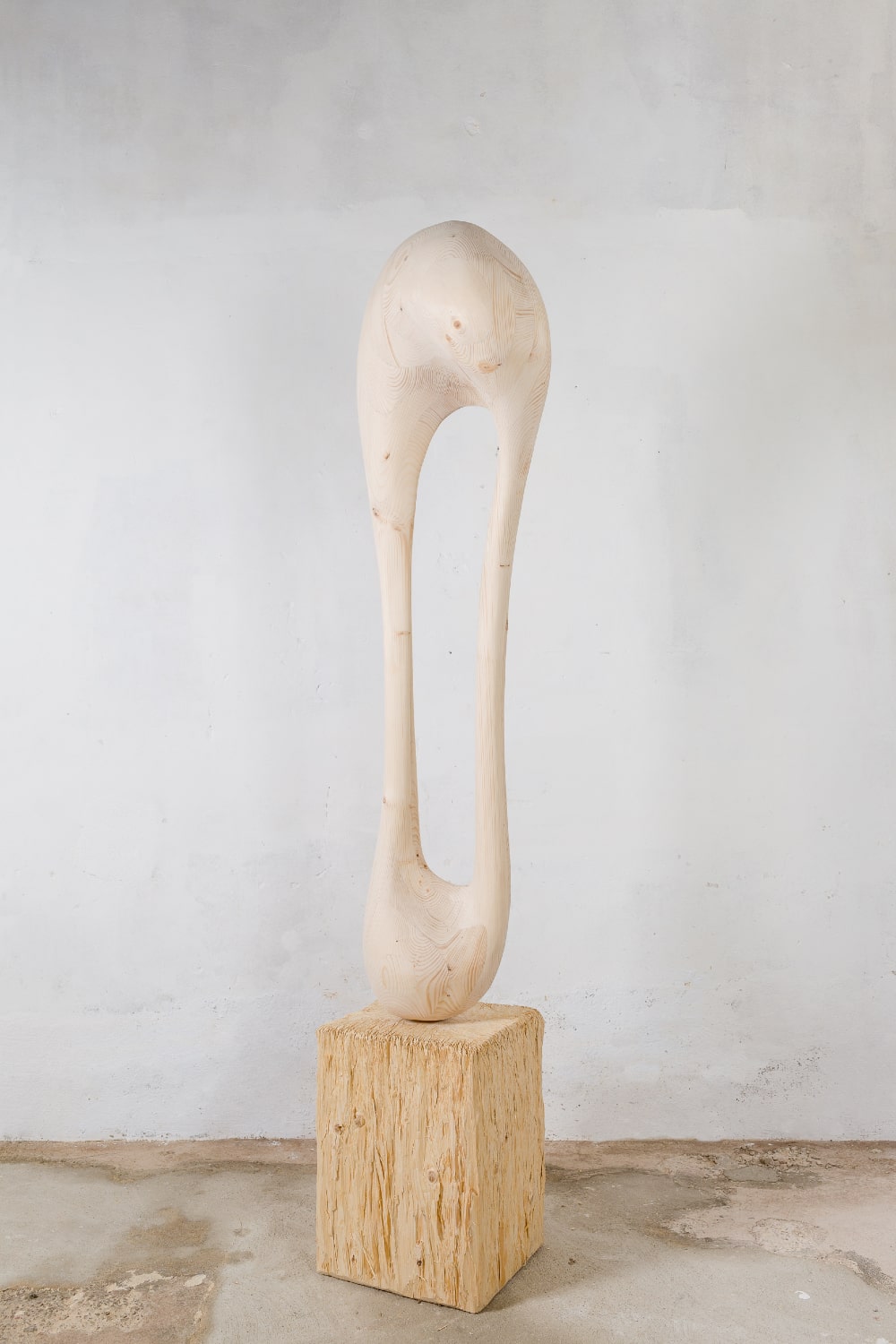

Born in 1974 in Uruguay, residing and working since 2004 in Palma de Mallorca, Spain, Martin Mas is a multidisciplinary artist best known for his organic sculptures and wall objects in wood. Having studied professional carpentry, wood sculpture, and fine arts, Mas has been combining a contemporary and minimal visual language marked by organic shapes with the age-old practice of carving wood. His metamorphic practice—encompassing various artistic disciplines, including painting, sculpture, works on paper, and installation—illustrates the alchemy of sculpting, transforming a natural and universal material such as wood into genuine and contemplative artworks in which the patina of the material itself remains visible. Today, we have the pleasure of discussing Martin Mas’s life and work.

Julien Delagrange: Dear Martin, great to have you on CAI for an interview. How have you been?

Martin Mas: Hello Julien, thank you for inviting me to CAI for this interview. I am a great admirer of your work, both as an artist and for the work you do on your CAI channel.

JD: Thank you very much for those most kind words. Let’s start with the beginning: growing up in Uruguay. What were your earliest influences that led you to pursue an art career?

MM: Since childhood, I’ve had a strong inclination towards art. In my mother’s house, there are still framed oil paintings I created at the age of eight. I was fortunate that my parents recognized and nurtured this inclination early on, encouraging me to paint from a young age. At fourteen, I began studying music (guitar), and I’ve continued pursuing both painting and music ever since. I embarked on a four-year carpentry program at the University of Labor of Uruguay (UTU) at sixteen. During this time, I also attended sculpture classes and workshops with various recognized artists, exploring different materials.

While working in carpentry shops during the day, I dedicated my evenings to studying wood carving at the School of Arts and Crafts. By then, I had already constructed my own workshop in Montevideo, complete with a wooden roof, walls, windows, and pillars. This marked the beginning of my deep affinity for workshop life, which has since become an integral part of my existence. At 22, I enrolled in the University of Fine Arts, an experience that proved pivotal for connecting with fellow artists, engaging in dialogue, and refining my artistic vision. Since then, I’ve remained committed to my artistic practice. Additionally, I’ve continuously enriched my understanding of art through reading, observation, and ongoing exploration.

JD: How has moving from Uruguay to Spain influenced your artistic vision and practice?

MM: The change was enormous. The first impact I felt was the access to public libraries, with the latest books that I had always wanted to buy or have. Upon arriving in Barcelona, I immersed myself in all the books possible, accessing all the public libraries. Additionally, you could borrow five books home for two weeks. That access was a big change.

It was also incredible to have direct access to the works of the great painters and artists that I only knew through books, and to be able to see them in person, in addition to the countless exhibitions, museums, and art fairs. Accessing that world of art was transformative.

Traveling and leaving your country and comfort zone always changes you and gives you another perspective. I would even dare to say that the same would happen to someone born here if they moved to South America. The learning would be brutal as well, and that would naturally influence your artistic practice crucially.

JD: How has your formal education, which encompassed carpentry, wood sculpture, and fine arts, shaped your approach to creating art?

MM: I would like to add another fundamental aspect to your question. Since I was very young, I have been in contact with rural life in the countryside in Uruguay. My father is an agronomist, and this led us to live in the countryside every summer. My life transitioned from the urban environment, filled with books, universities, studios, skateboarding, music, and nightlife, to a humble rural life with few amenities, lacking electricity or running water, where I milked cows and rode horses. Growing up in these environments, I developed a profound appreciation for working with my hands and for the simplicity and authenticity of simple life. This amalgamation of different perspectives on life has been fundamental in shaping my artistic practice.

Carpentry provided me with an academic, formal, and structured approach to working with my hands, guiding me through the process from initial drawing to material realization. This methodological approach extends beyond woodwork to encompass any material or project. I acquired skills in planning, drawing, and executing tasks, which I later applied to various materials in my sculpture work over two decades. Wood carving granted me the freedom to experiment with the material, while my studies in fine arts served as direct influences, aiding in the cohesion of these experiences within the language and context of artistic expression.

JD: A couple of years ago, many of your works were not carved from wood, as you have used stainless steel, bronze, aluminum, and more. It seems that around 2022, your focus shifted convincingly back to wood as your characteristic medium. What initiated this shift?

MM: Indeed. As I mentioned earlier, my initial foray into sculpture was through wood carving, and I dedicated myself to it for a time. However, my desire to explore new horizons and my growing interest in contemporary art led me to experiment with other materials, completely setting aside wood. I associated wood with craftsmanship, tradition, and classicism, and I did not see innovative potential in it for my work. My pursuit was to look forward and explore the new, and wood did not serve that purpose, so I abandoned it, almost with disdain, I would say.

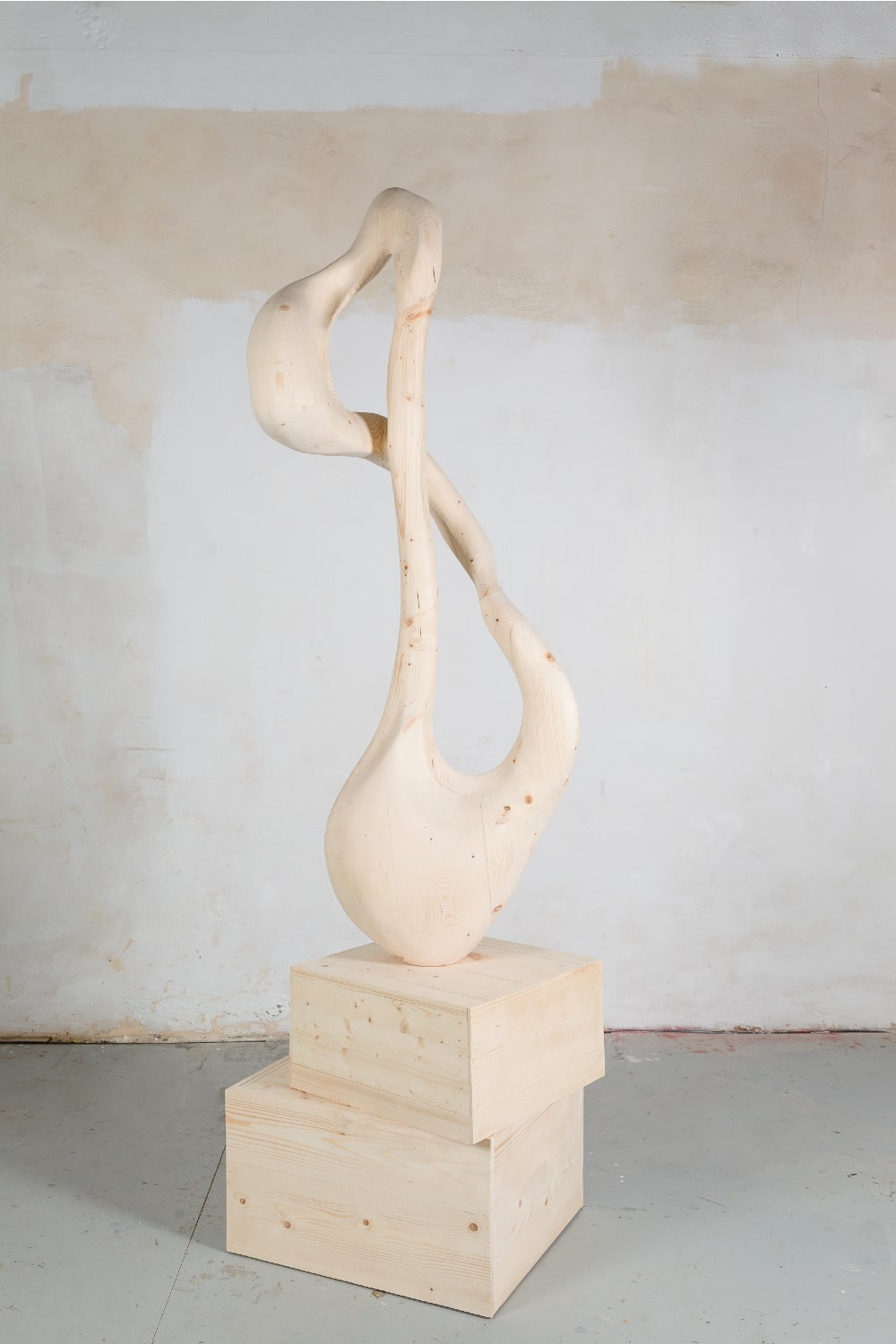

However, something interesting happened in early 2022. Alongside my studio for the past 15 years, there had always been a carpentry shop operating since the 1950s. When the owner retired early that year, the place closed permanently. It remained inactive for several months. One day, I found the door open and went in. The sensation that overcame me was strange, somehow distant, yet familiar. As I observed the old machinery, I recalled my beginnings in Uruguay three decades ago. Determined, I left there with a decision to rent the space and work there, expanding my studio. Two days later, I was inside. I created two medium-sized wooden sculptures and developed a well-structured, highly visual project with small clay models for a solo show at the gallery based on wood. Six months later, I held the exhibition, and it was a success.

This was a true turning point. Working with wood after three decades gave me a sense of freshness and familiarity with the material. I came from more than two decades of experience with various materials and approached it from an external perspective to wood. Instead of starting from the concept of wood, I took wood with all its intrinsic characteristics to express external concepts born from art itself. This allowed me to approach wood with a renewed vision, seeking a contemporary language of clear, simple, and direct lines, organic shapes, vibrant colors, freshness, and luminosity, all with a contemporary outlook and a renewed reflection on a material I had known since childhood.

JD: Could you walk us through your process from the initial concept of a piece to its final execution?

MM: Of course, I’d like to clarify that ideas stem from the realm of thoughts, self-generating, and feeding off themselves and various stimuli. Every morning, I sit in a café for 30 minutes and read, draw, or write (I write down thoughts and ideas just for myself). It’s like warming up the engines. Then, I head to the studio, do my work attire, and begin working. It’s like going out hunting: the hunting ground is your own mind, where you search for ideas. This habit is the true combustion engine that drives the creation of artworks. Stimuli can come from books, ideas, conversations, past exhibitions, and more.

As an artist, your task is to process this external world, filter it through your own sieve, and generate “something new” from it. Something that didn’t exist before. Something that is more than just the mere sum of its parts; it’s a separate and independent entity that no longer belongs to you. It’s more like a photograph, a daguerreotype of your vision and stance as an artist in the world. Over time, you develop your own iconography and visual language. A significant part of your work as an artist is to create this collection of daguerreotypes that resonate with you and speak for you. Creating a material alter ego, so to speak.

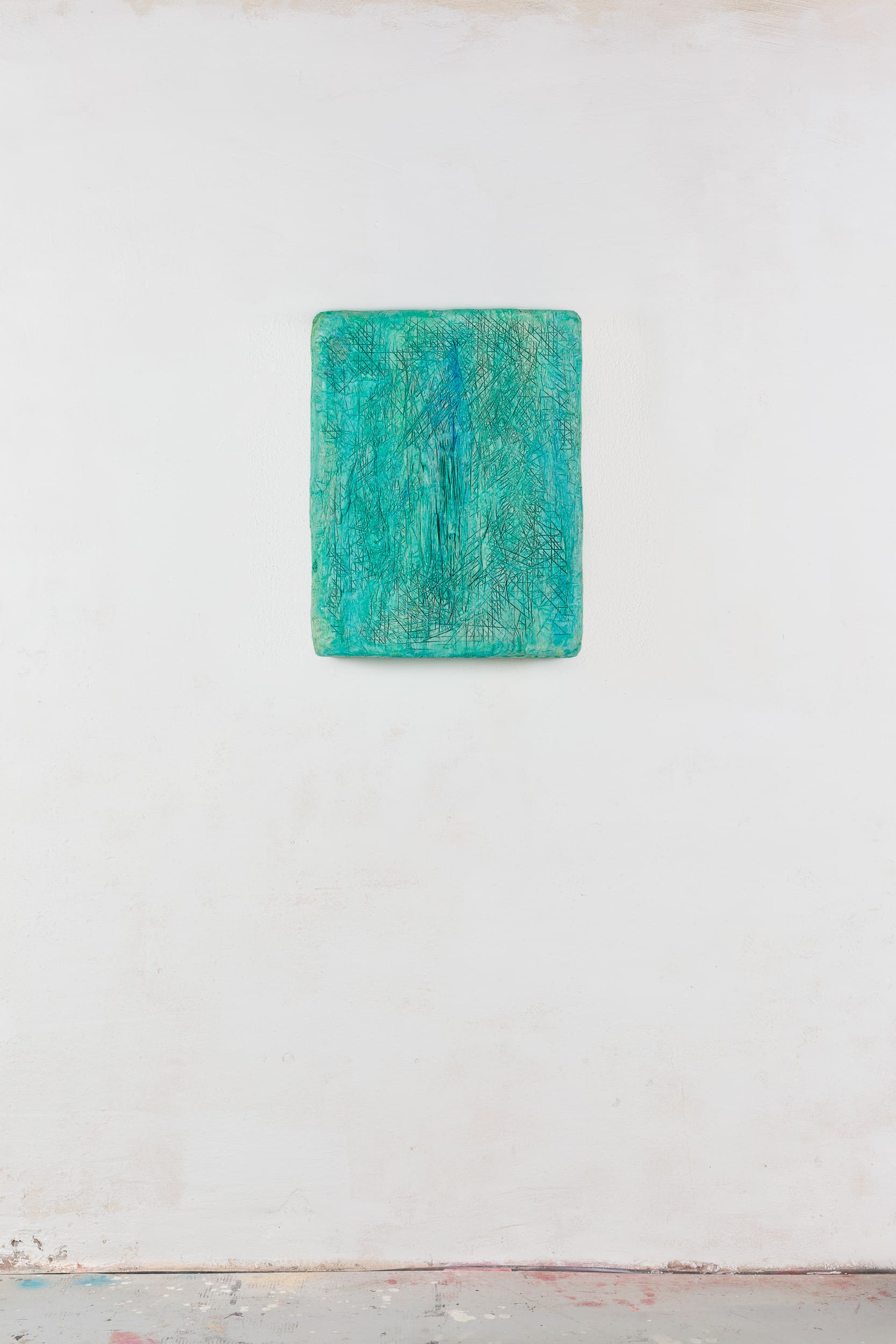

JD: Let’s start with your paintings first, or should I call them wall sculptures instead? These wooden tableaus have a distinctively minimalist aesthetic. Yet, in comparison to your contemporaries, such as Imi Knoebel or Ugo Rondinone, your surface is not flat and unicolored. It consists of various subtleties in texture, color, tone, transparency, and more. Could you expand on these wall objects?

MM: These are sculptures as much as paintings, but “wall objects” describe them well; it’s a more open term. As I mentioned before, this series, based on wood as a leitmotif, utilizes minimalist elements with clear, simple, and direct lines, sometimes combined with vibrant and fresh colors. I always use light wood for my work; I don’t use dark wood because they diverge from my purpose. However, I try to highlight the importance of the underlying medium. It’s not paint; it’s stained wood. To achieve this, I use diluted oil paint, which I apply in successive overlapping layers.

This staining or tinting, akin to watercolors, allows the brightness, transparency, and subtleties of texture to show through. It’s not just a simple layer of color; I want to highlight the medium in which the artwork is created. I feel these wall objects as color boxes, packages, containers of concentrated ideas at a point, like a cluster of materialized ideas.

JD: What are some of the more challenging aspects of working with wood, and how do you address these challenges? How can you balance, for instance, a minimalistic aesthetic with wood’s inherently unpredictable nature?

MM: I would like to emphasize that there is a significant technical aspect to my work. These aspects are constantly evolving. My pieces do not originate from a single block of wood; instead, they evolve as I create them. I add, remove, and cut parts and pieces as I progress through the creative process. The works are never truly finished; they often rest in the studio for months, half-done, or even after being completed, they can be revisited and modified in various ways, such as cutting, painting, or subjecting them to more aggressive processes like chopping with an axe or chainsaw, burning, charring, staining, or immersing them in tinted water or oil, then exposing them to sunlight to induce cracks.

This allows me to explore the material, technique, and ideas to their limits. Additionally, I am working on an installation using all the wood shavings I collect, aiming to make the most of the material. Sometimes, I seek to soften the works, adopting a more minimalist expression, as you mentioned. This minimalist approach is also reflected in the use of color, often employing a single tone in each piece. What I mean by this is that the work is constantly changing. It is as if all the pieces are part of a single body, a continuum, where each work is an integral part.

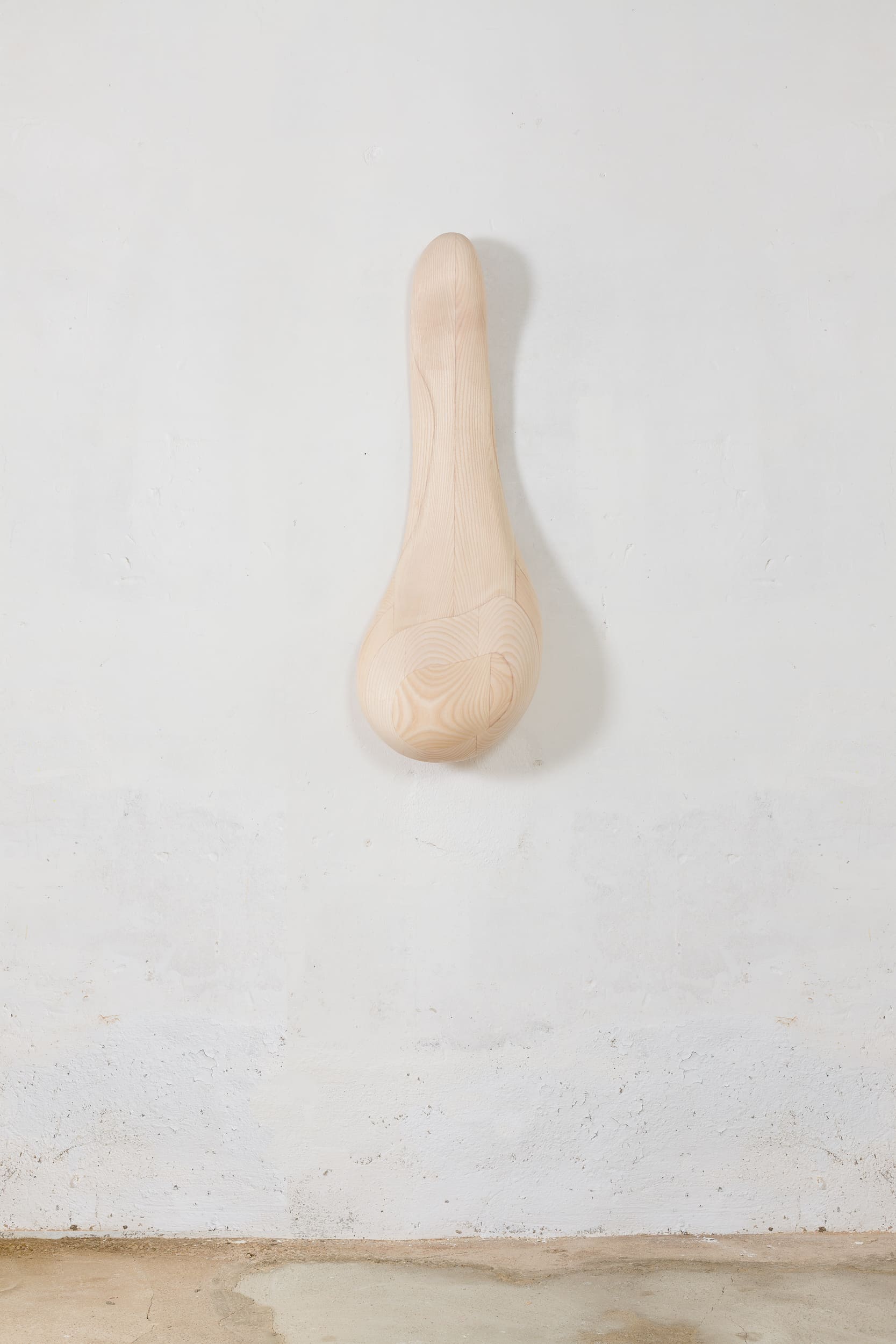

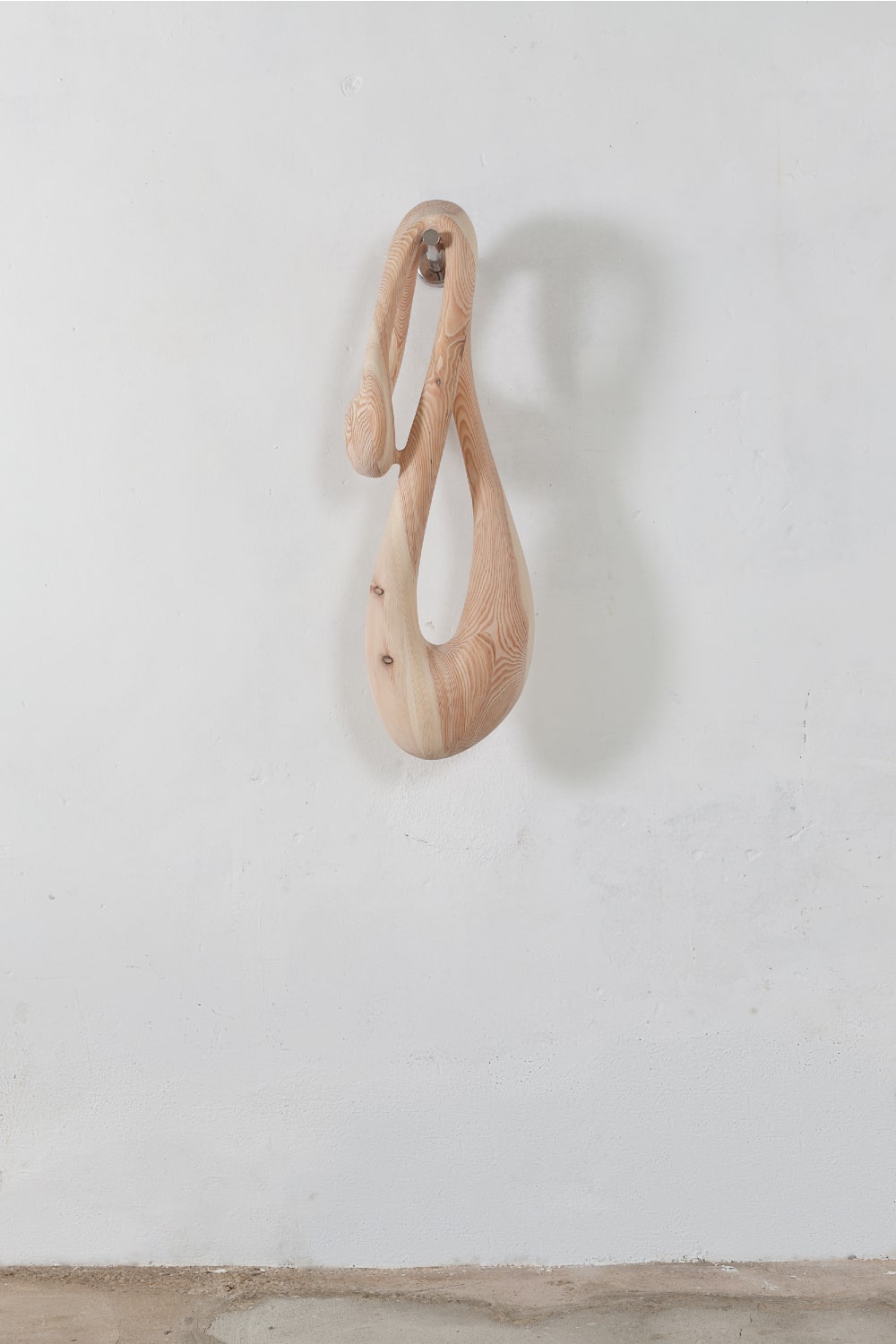

JD: Beyond the material presence of wood, the organic is also present in the form. Some of your wall objects bulge organically, and your sculptures consist of almost sensual organic movements. What is it exactly that draws you to create these organic shapes

MM: Wood interests me because of its intrinsic qualities. It is a common, unpretentious, and familiar material. Wood has been present throughout all human cultures, playing a fundamental role in them, from building houses and tools to creating fire and statuettes, what could be called proto-art. It is an organic material still present in all social strata today, from the humblest to the most advanced contemporary architectural designs. I love that.

I have always been intrigued by the change of state of things. In physics, for example, by changing the conditions of the environment and the context we believe we know, elements can transition from solid to liquid to gas, and if the conditions are extreme, to plasma, a soup of atoms without structure that reorders into another reality. I am interested in making the ordinary surprising again by altering its usual conditions and awakening new questions. I like the pieces to be recognizable as wood but revisited from a new perspective.

On the other hand, I have always been fascinated by the sensual play of transformation, for example, in the Renaissance, turning marble into skin and flesh. In Michelangelo’s La Pietà, for instance, the folds of the skin and the languid body of the dead Christ with his head to one side are examples of this transformation. In Bernini’s The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, the floating robes and the languid sensuality of Saint Teresa’s representation are pinnacles of art history.

It’s not that my work revisits these styles or pieces directly; my interest lies more in transformation and movement. I am always intrigued by this ambiguous play of transformations and the ability to see the ordinary with new eyes, as well as the sensual play of transforming something inert into something alive. Ultimately, creating art is about bringing the language of the world of ideas into material form, making it flesh.

JD: Would you say sculpture is at the center of your practice?

MM: Absolutely! I have a special interest in matter and how it interacts with us. A clear example is my paper-based work. For instance, I start by staining papers with charcoal, and gradually, I join and glue them together to form a three-dimensional mass of paper with relief. The same happens with my paintings. I begin with the idea of creating a painting, but gradually, they acquire relief and mass, becoming more like wall objects.

Sculpture coexists with us in our same reality; it lives with us; it is there, present. You have to look at it from different angles; it is affected by light and has both visual and physical weight. I find it fascinating that “everything can be sculpture,” like Duchamp’s urinal, where he took an ordinary object into an artistic context, provoking a reflection on the nature of art, about what art is and what art is not, forever changing its perception. This could only have been achieved through sculpture, through a three-dimensional object.

JD: What kind of reaction do you hope to evoke with your work?

Reflection, pensiveness, silence, inner projection, introspection. I don’t want to impose conceptual dogmas on anyone; I just wish the works to initiate a personal and silent dialogue with the viewer.

I aim to evoke a thoughtful, reflective attitude from a contemporary language and perspective. I work with a blend of primary languages and abstract forms, combining elements considered basic, primitive, or universal, such as breaking, cutting, joining, and burning, sometimes tinted with bright colors. I use soft and light colors along with organic shapes, juxtaposing natural forms with artificial colors to create a fresher and more vivid aesthetic. At the same time, I seek to blend a certain primitivism and rawness within a contemporary context.

JD: You have exhibited your works worldwide, from Buenos Aires to Palma de Mallorca and from New York to Seoul. What advice would you give to young artists who are interested in working with organic materials and aim to embrace a multidisciplinary practice?

MM: I would emphasize the importance of trying all possible disciplines and setting aside preconceived ideas about what each technique or material can offer. Often, one searches for a personal style and, upon finding something that works, sticks with it. Immediate commercial success can become a long-term trap. Changing after that can be difficult, leading to stagnation. I was fortunate to go through tough times and years of poor sales.

Nevertheless, you keep going. Artistic practice cannot initially depend on whether you get paid or not. Art is a way of being, thinking, seeing the world, feeling conscious of the world around you, and finding an identity. In the long run, you will need money, but being an artist is like breathing: you don’t need someone to pay you to breathe. You do it out of necessity.

Over time, you find a gravitational center where all your experiences converge. All that scattered material begins to cohere, forming structures and a body of ideas. When you find that center, you no longer think about where you’re going. You enter the studio and simply move, turn, and work. That’s when you start finding your words, your language, your own iconography. In summary: try every material and technique that crosses your path without expecting anything in return. Do it for yourself; it’s an internal dialogue. The rest will come in due time.

JD: To conclude, are there any upcoming projects that you would like to share with us?

MM: There are several projects in mind, but rather than discussing specific projects, I would like to focus on the questions and doubts I’m exploring in my work and the changes they entail. As I mentioned earlier, I have worked with various materials, such as silicone, paint, aluminum, and stainless steel, over the years. While color has been present in my artistic practice throughout these years, mainly with aluminum and silicone sculptures, I have yet to explore its potential in the context of wood fully. So far, I have focused more on form and natural colors.

At this moment, I am revisiting my work through the lens of color, trying to delve deeper and adapt it without obscuring the inherent qualities of the wood. I already have an exhibition scheduled for the end of the year, as well as ongoing discussions for projects in both Uruguay and Colombia. Additionally, I am working on expanding my artistic presence in Europe. Undoubtedly, this year represents a period of significant changes for me.

JD: Thank you so much, Martin; it has been a pleasure!

MM: Thank you very much, Julien! It’s been a pleasure as well.

Last Updated on February 12, 2025

About the author:

- Tags: HOME