Born in 1989 in Rădăuți, Romania, and currently residing and working in London, Mircea Teleagă is best known for his humanless scapes painted in oil and acrylic on canvas. Balancing between landscapes and urban environments, the artist approaches the application of paint almost as if a shapeshifter; from virtuously to vigorously, opaque to transparent, and lucid to destructive.

By doing so, in Teleagă’s practice, painting becomes a tool to capture impalpable spaces, as he is interested in the notion of emotional ownership of places—an outer world depicting or reflecting an inner world. Born in the year of the Romanian Revolution, Teleagă’s youth and background growing up during the aftermath of Romania’s uneasy transition from communism to capitalism form a battlefield where personal memories collide with collective history.

Earlier this month, the MFA graduate in painting at the Slade School of Fine Arts in London presented his latest works at Unit 1 Gallery Workshop in the English capital—another chapter in the development of the Romanian artist’s intriguing oeuvre. So today, we have the pleasure of having a chat about his latest show, his artistic ventures, and his journey as a painter—literally and figuratively speaking.

JD

Dear Mircea, terrific to have you for an interview. Welcome. How have you been?

MT

Thank you very much, Julien. It’s been a busy period. I am delighted to be here.

JD

You were born and raised in Romania, where you have spent most of your life. However, your life as an artist has predominantly taken place abroad. You studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, graduating in 2016, followed by a two-year studio residency at Sarabande in London. During this period, we also encounter the beginning of what one could call your mature oeuvre as an artist. Would you say this period and early achievements were essential? And feel free to talk us through your education and search for an artistic language and identity.

MT

Yes, I grew up and lived in Romania until I was 21, after which I moved to the United Kingdom to start my formal fine art education. I was fortunate to get a scholarship in 2014 to study at the Slade, followed by a residency that provided a studio too. A lot of things happened at that time, all very fast. The time I spent at the Slade was crucial. You’ve hit the nail on the head with the words the beginning of maturity. I didn’t know it then, but such vital landmarks were set for my practice. I was experimenting a lot during those times, and my path didn’t seem that clear from the beginning. Still, it was a period of intense questioning, stripping everything to the bone and working towards building a durable foundation for years to come.

There was quite a lot of pressure, I guess, from the outside and, even worse, from the inside. I remember; after finishing the course, I was lucky to have a few things happening. I was doing this summer residency at the Slade, and I made this painting I immediately recognized as something I had been after for the past year or two. It’s funny, but it took three months after graduating before I started producing work that fully felt like mine. Some massive gates suddenly opened, and this huge mass of stuff poured through. Just after that, I went to Hong Kong for three months—which was a turning point for me—I could spend a lot of time talking about that. A lot of things are still brewing from those times. I came back in late 2016, and that’s when I started the residency at Sarabande, and for the next two years, I had time to distill and process. This is how the two solo shows came about, quite soon, one after the other, in 2017 and 2018. There was a lot of stuff coming out. Overall, it was a period when I did a lot of growing up.

JD

At this point, you were also experiencing what it means to be an immigrant. Living in a foreign country and disconnected from the aforementioned emotional ownership of a place—in this case, a place called home. Would you say this was one of the impelling forces to spark your interest in how places have emotional or historical ownership attached to them? An abstract and elusive concept you experienced vividly?

MT

Strangely enough, realizing I was an immigrant came sometime later. I was so preoccupied with painting that it somehow went unnoticed. Maybe because I assumed it was going to be temporary. It was one of those things you notice at some point and wonder why it did not strike you sooner, what had been happening for a long time. The notion of home has been slowly disintegrating and changing over time. It may have to do with the moment I left Romania. You do notice people behaving differently when you are an immigrant, but that never bothered me as I was always clinging to painting. And I justified everything in terms of painting. For instance, I started noticing these two countries’ different attitudes towards urban or rural spaces. I believe the space or area you spend a lot of time in—or next to—does have a significant impact on your mind.

This questioning of the emotional ownership of memories and places started way before, when I was a lot younger, even though I wasn’t aware of it then. My parents were planning to move from the town we were living to a nearby village. My father wanted to build a house in this beautiful place we visited every weekend, especially in the summer. That’s when I started to connect with the surrounding landscape and forest. Later, when I was about 13, during our move to the countryside, I was hanging around and helping out when the foundation of the house was being laid. I struck a metal object with a spade in the ground, and it turned out to be a very old and rusty tank or artillery shell. We found bullet casings and other things, but that’s when it happened in my mind. I realized that these places, which I thought somehow belonged only to me, actually had a very complex, and more importantly, separate, life of their own.

Ironically this was going to be the foundation for my future reflections. I acknowledged it as a personal foundation more recently. Things started to become very layered, like a reversed psychological archeological site. When I spent some time in Hong Kong years later, I discovered yet another place that somehow owned a small piece of my home. But this time, the brutalist architecture was the trigger, with its concrete that doesn’t age that well. It’s funny how this act of remembering and sharing personal memories always takes something away, like a toll.

Slowly but surely, what you think to be your identity is being chipped away if you pay close attention, as you realize to be a part of a much bigger thing—or much smaller, depending on how you want to look at things. Recently, going back to Romania, I noticed many things have changed. This happens to everyone who goes back to where they grew up. Things stay the same in your mind, and you see the changes when confronted with them in real life. Every time I go back, there is this odd process of updating, which consists of acknowledging and accepting change, not any improvement.

JD

Clearly, your home country has a prominent place in your work.

MT

I may have just confirmed this to myself recently. Ultimately, my work is autobiographical. I cannot see how it could not be. For that matter, I see all my work in those terms. The places I grew up around have had a significant impact. Growing up next to huge voids was terrific. I have grown a very particular sensibility now and attribute this characteristic to these places. It happens when you take in a place and let it mold you, leaving its imprint on you.

JD

All these influences seem to culminate in a first milestone show in 2017 and 2018, with two solo exhibitions at the Sarabande Foundation titled let it burn and Presence, in chronological order. Here, we encounter your characteristic haunting landscapes with a strong emphasis on the materiality of paint. An accumulation of a vast array of techniques and methods for applying and manipulating paint on canvas. Could you talk us through your methodology and creative process as a painter and why it is important for you to add this materiality and variety in texture to your paintings?

MT

Yes, it was around this time that my works focused on a singularity and monumentality of a central figure. Regarding my relationship with the medium of painting, I think I could really go on about this forever. Paint as a material has always fascinated me. Overall, I have been interested in the materiality of things and how those things have a distinct look and feel. Take film grain, for example. I consume a lot of film; most certainly, my primary visual input is film, and at some point, I almost chose to enter the cinema industry. But coming back to the question of material, the film grain was something that attracted me immediately and made it very compelling for me to look at, and I started paying a lot of attention to how films from the 60s, 70s, 80, and early 2000s look from this point of view. They all have a unique look due to the technology of the time. This particular look, caused by the medium, becomes part of the work’s identity and cannot be replicated elsewhere.

From this point of view, I see painting as a complete circle. Technologically we expect no significant breakthroughs, and as a painter, I work with what I have, which is a relatively concise list of things. It mainly consists of some colored dirt or metal on a piece of fabric. It’s fascinating to think that is all there is, and it is very liberating to know there is no need for technological improvement. Amazingly, we can accept it as it is. And, even more fascinating, in this time of rapid technological development—updating and replacing the obsolete at an incredible pace—I find it very comforting to think that someone a few hundred years ago used the same tools, in the same way, to make an object very similar to the one I am making now, despite all the other differences.

Keeping some of these old, obsolete things around is fantastic. There is a particular connection being kept alive. Maybe it speaks more about the journey rather than about the destination. The materiality of paint is something I cannot not engage with. What one looks at is, first of all, a painting, and it must be satisfying as a painting before anything else. It is part of its uniqueness and part of the reason for it to exist in the first place. What I am trying to say is that I think there is a strong link between how something is made and what it has to say. If you think about Egyptian sculpture or the Italian paintings just before the Renaissance—like those of Giotto—you see a particular kind of transcendence almost, where the message is conveyed almost through osmosis, a very non-didactical way of saying things. And I do not think one needs any theoretical background to see these things. They are very experiential.

I believe in the medium of painting, and for a painting to be successful, there is a need for a careful balance between what is being said and how it is being said. They need to have the correct weight to support and balance each other. You were right earlier; these two shows, let it burn (2017) and Presence (2018), are the first mature manifestations of my practice. They both revolve around this alchemical relationship between the matter and the image—or the illusion if you want.

JD

In these pictures, we encounter trees and the sky time after time. Yet, these landscapes are not romantic nor wild, as they show traces and structures invented and constructed by mankind—just when one was almost about to forget; hence not a single human figure is depicted. A doorway, street lights, or an industrial structure. What is the origin of these in-between scapes, views, and places entangled between the natural landscape and the urban?

MT

I have always been very interested in this border world. Looking back, I can see that I have always lived on different borders, physical or fictional, where two very different worlds meet. Historically we were taught that Romania had been a border or buffer area between East and West. Within the country itself, my hometown is very close to the border with Ukraine—in that town, the apartment block I grew up in was on the city’s outskirts, so I could see a lot of fields from my window as the city ended there. Spiritually, the society I grew up in was one of an uneasy transition from communism to capitalism, and I could notice a lot of things changing there. I gradually saw giant concrete mammoths slowly disintegrate when no one was around, and in this sense, I grew up surrounded by a lot of decay, factory ruins, or places-soon-to-become-ruins.

Being born in 1989 in this particular place of the world has had its influence, too, as many people refer to a whole other world I never knew directly. Earlier, we discussed growing up next to these vast forests. There’s another border right there. The origin you are asking about may come from these things. I was focusing on presenting glimpses of solitary and lonely places. I am happy that you specified that they are not romantic. I love romantic painting, which has always influenced my work—I even wish I could do this kind of painting. It is almost like I try, but I must accept that this sort of painting cannot find a place, and the result of this process is this border world.

JD

Over the years, you have also painted various interior spaces. Could you expand on the relationship between the interior and the exterior in your work?

MT

The interior scenes tend to be less believable as physical places and gravitate towards the non-corporeal. My landscapes hint at that too, but I believe the interior places show this departure toward the non-physical most clearly. The focal point is often the boundary between the two, and we are again talking about the liminal, the border world, inside versus outside. The relationship is quite direct. You can’t have one without the other, and you can only appreciate both through proximity and comparison. Having one means having two, and having these two, means having a third—Janus, the limit between the two. That undefined liminal is what fascinates me.

JD

Even with these interior spaces, and regardless of your color palette, your paintings always seem to carry a specific aura or atmosphere—an amalgam of the magical, the surreal, the dream-like, and the eerie. Is this a premeditated strategy or more a natural result?

MT

Both, in the sense that I have noticed the natural tendency to go that way, and I then nurture that potential. It goes back to this non-verbal quality of the medium. It goes back to this moment when the medium is in perfect sync with what is being said, and there is total immersion. I love it when the works look otherworldly. It means they are manifesting a place of their own and are not surrogates. That is what I am after in the end. To have the works ooze out and be their own thing. If you can look at any piece of art and get completely lost in it for a few seconds, forgetting everything, that’s where it’s at. That is the moment of total abandonment I am after as a viewer—and as a maker.

JD

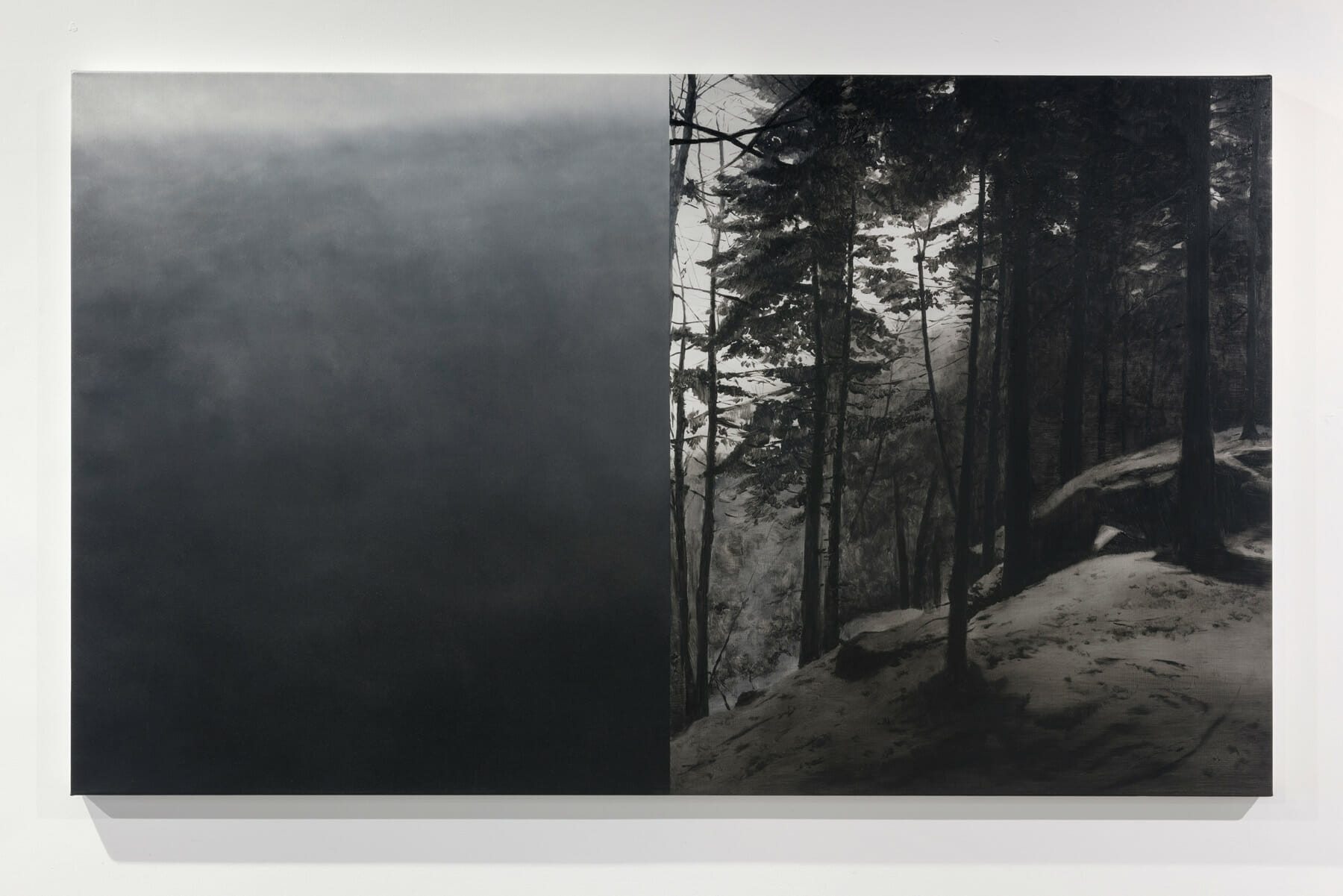

In your most recent pieces, showcased during your solo exhibition Locus Solus at Unit 1 Gallery in London, forests and quasi-abstract gradients come to the fore. Dislocation, isolation and the enigmatic atmosphere in your paintings seem to increase in volume and power. Could you talk us through the exhibition and this latest series of works?

MT

The body of work in the Locus Solus exhibition is the result of the last two years’ work. I focused on this motif of splitting the canvases into two areas out of instinct initially, but then it started making sense on multiple levels. The paintings were suddenly about more than representations of forests, highlighting an unseen side of them bluntly. I was thinking more about the non-physical I mentioned earlier. This motif presented itself, and I decided to expand on it by making a series of works.

The ramifications touched many of my interests, and the works started talking about memory, immersion, loneliness, solitude, and painting and image. Some were initially painted in Romania, as I wanted to see what it felt like working there, close to their place of origin. I shipped them back to London, finishing them and working on new ones. I liked that this decision was justified in various ways and made sense in my practice. I want it to make sense as part of my painting language and not become preachy.

JD

Intriguingly, you juxtapose the forest’s depth with the abstract gradient’s flatness.

MT

I am not sure it is about an abstract area and the forest. It’s more about the picture as a whole. If you want to follow this train of thought, it’s all abstract. The painted forest is nothing more than a collection of marks. No painter has ever actually painted everything they depicted. At a certain level, they are all just abstract marks that look like something. You do have to take both parts of the canvas in simultaneously. You cannot not see them in the same field of vision, and this is something I love about them: you take turns in focusing on each side.

However, the way our sight works makes it impossible to focus on both simultaneously, so you take turns. The part you focus on is next to this hazy blur you cannot eliminate. It becomes very dreamlike once you look at them for some time. The grey start to shimmer, and they become really colorful. It’s like hearing your phone ring while sleeping. The noise is not loud enough to wake you up but loud enough to enter the dream and find its own twisted logic. And then you swap, and they change roles.

I have been fascinated with this sort of negative space for a while and wanted to give it a more present role. It is the sort of space we often take for granted and don’t pay much attention to, but it defines everything we see. I often found the periphery—the surrounding area—much more charged and engaging than the epicenter. And the funny thing is that it manifests while you are not looking at it. It glows with a lot of color once you let it be, don’t give it much attention, and take everything in as a whole.

JD

To conclude, the omnipresent question in art and the life of a painter is; what’s next?

MT

I just returned from a three-month residency in Norway and have been working on a new body of work there. I was there from January until the end of March (2023), and I came back to London just in time for my solo show. I wanted to begin a new series of works, but starting from a few things that were not fully explored. Overall, it was a great experience, and I want to see how this new body of work will turn out. It will be a bit different from what I have just shown now, as I will focus on a more meaty side of my painting, as you said earlier. I feel like watching sediments settle in a fish tank, and I am curious about where this will take me. Having spent three months in a remote place with few people around was strangely beneficial for my work, although not unexpected.

JD

Thank you so much for your time and paintings. It has been a pleasure, and we look forward to discovering what you have in store for us.

MT

Thank you very much, Julien; it’s been great talking to you.

Last Updated on November 9, 2024