A chopped-up shark, a split-open pig on movable rails, a decapitated cow, and a calf with six limbs. Since March 9, 2022, more than twenty iconic examples of Damien Hirst’s groundbreaking and notorious formaldehyde sculptures have been showcased at Gagosian’s Brittania Street gallery, dating from 1991 to 2021. But how well do these ‘vintage Damien Hirst’ works stand the test of time – not only from a conservation point of view but also art historically?

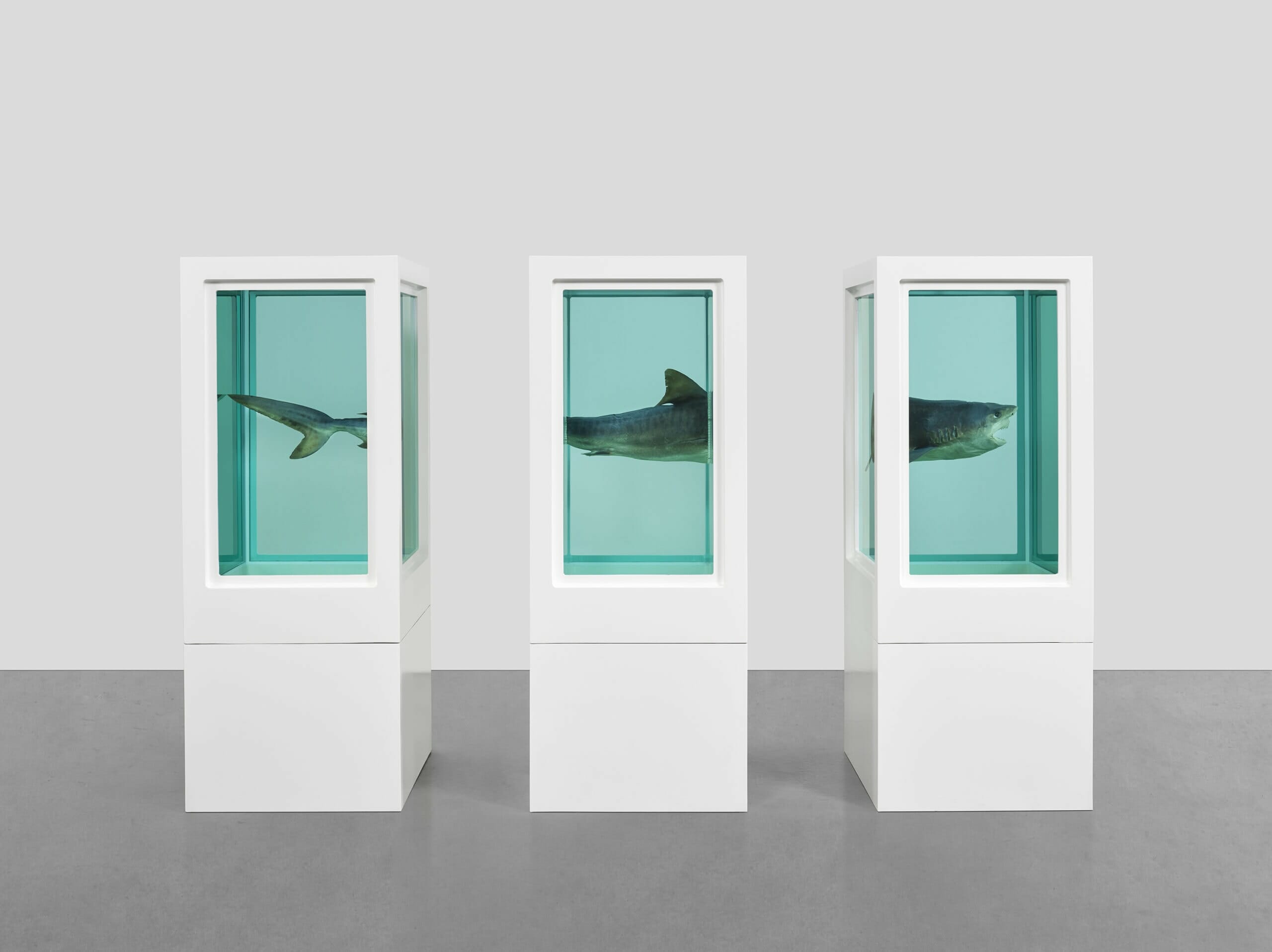

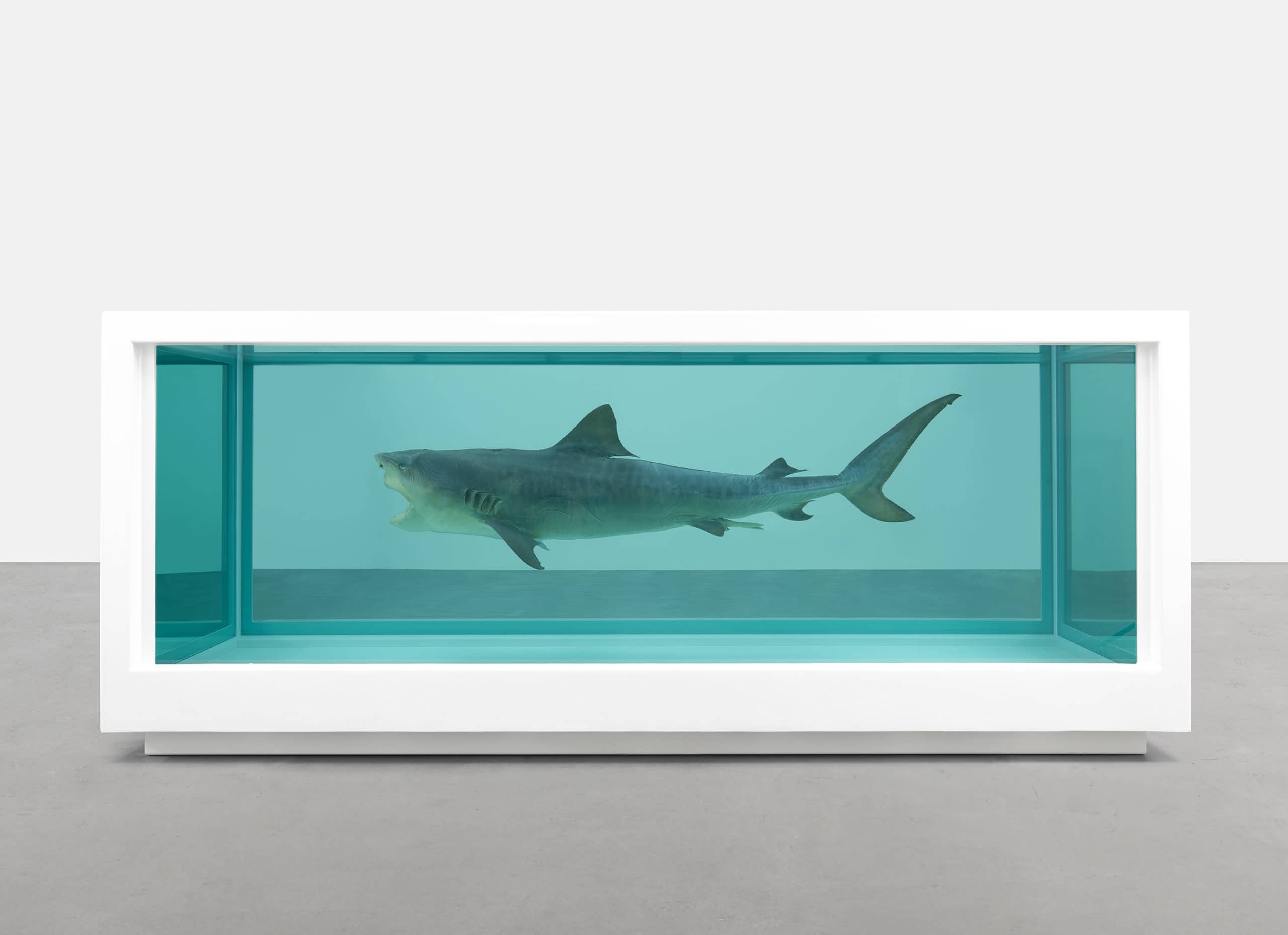

Damien Hirst (born in 1965 in Bristol, residing and working in London, the United Kingdom) rose to fame in the late 1980s with his often shocking artworks, pushing the boundaries of not only good taste and the morally acceptable but also of contemporary art. In 1991, the YBA poster boy shocked the world with arguably the most iconic sculpture he ever made, titled The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living. A fourteen-foot tiger shark, ready to strike you down with a single snap of his jaws. However, the shark sculpture is not made from marble, wood, or wax. It is as real as it is dead, preserved in a tank of formaldehyde, a chemical compound made of hydrogen, oxygen, and carbon, best known for its preservative and anti-bacterial properties. The shark in question would be the first of an ongoing Natural History series driven by Hirst’s fascination for life versus death and science versus religion.

Today, three decades later and with a different Zeitgeist and frame of reference, we return to Hirst’s notorious formaldehyde sculptures after a series of less adventurous dots and cherry blossom paintings. In 2022, it was an understatement to say Hirst’s dead animals might spark some controversy and consternation in public opinion. Animal rights have never before been as prominent as today. Still, even though Hirst is not the only one using dead animals in his profession, he shows the coldness and brutality of death with unseen honesty. His formaldehyde sculptures are more than just a gimmick of preservation and a quest for sensation. At the same time as we are shocked and incensed, we are also intrigued. We are confronted with death, much closer than we are used to. Life versus death is, and always will be, one of the greatest dichotomies.

We lure at those dead carcasses, feeling sorry for the passing of their soul. Still, simultaneously we are investigating the earthly remains – bones, flesh, and even bowels – with our very own eyes. Whereas many might wonder: “Is this art?” The more important question coming to the mind of any beholder would be: “Is this life?” – or rather – “Is this death?” Even though their bodies are isolated and preserved, we are confronted with the inevitability of death and decay. A second major dichotomy in Natural History is, without any doubt, science versus religion. Traditionally speaking, both terms are opposites. Religion ends where science starts. However, with Hirst’s shocking sculptures, both spheres seem to merge into a new synthesis, effectuated by art and art history. In fact, why be surprised? From a historical perspective, art has always had a very strong connection with both science and religion. A junction Damien Hirst eagerly tackles in a subtle or often very distinctive manner.

Hence, besides art historical references to Francis Bacon’s two carcasses in the backdrop of Figure with Meat from 1954, or the similarities concerning the esthetics and structure of the white skeleton of the glass tanks, reminiscent of Minimal Art – think of Sol LeWitt’s structures – Damien Hirst implements a religious iconography in order to emphasize the juxtaposition of science versus religion. For instance, Cain and Abel from 1994 show us two calves next to each other – isolated in separate tanks. The title refers to the story of the two brothers Cain and Abel from the book of Genesis, in which the first would kill the latter. A tale about death, jealousy, and divinity as we approach those two poor calves as brothers. Or what about The Ascension from 2003? Hirst presents a calf with six limbs vertically in the tank as if it’s been swirled up to heaven. Here, the British artist tackles the absurdity of the afterlife, using the pictorial tradition of the assumption as a visual apologia.

Arguably one of the more shocking sculptures – besides the flayed and crucified cows – must be The Beheading of John the Baptist from 2006. A brutal scene and a favorite subject of many masters throughout art history think of Caravaggio’s eponymous masterpiece at the start of the 17th century. A decapitated cow is found on a white-tiled floor. Its head is lying on the butcher’s table, accompanied by colorful knives. Above, there is a clock sitting still at 11:53 as Hirst reflects on the halt of time due to death and its finiteness.

Life, death, religion, and science. All four key themes of Hirst’s oeuvre are celebrated in these extraordinary sculptures. If an emotional reaction in front of an artwork is an indication of success, it is safe to say Hirst succeeds in inciting our senses and emotions. The inconvenient truth is we are not only shocked by the raw depiction of death and mortal remains but we are also shocked by how we continue to be utterly fascinated by death. No matter how civilized or morally developed we are, the inherently human desire and our fascination for life’s great dichotomies seem to be as inevitable as death itself – as is the lasting impact of Damien Hirst’s formaldehyde sculptures.

Last Updated on May 23, 2023