So you’ve just finished a new artwork and are now stuck on what to call it. Do you simply go with Untitled and be done with it? Should it be something poetic? Or what about a more cryptic title? Or will that be complicated to comprehend? For some artists, titles can feel like an afterthought, but in reality, they’re one of the most powerful tools artists have. The right title can create tension, hint at a story, or completely change how someone sees your work. It can enhance your work and even your more expansive oeuvre. However, there are also some common mistakes you want to avoid as an artist at all times. Therefore, in this article, we’ll be discussing practical tips for titling your art, drawing from real examples and strategies by established artists.

1. To Title or Not To Title, That Is the Question

First and foremost, do all artworks need titles? Not necessarily. “Untitled” is a valid title and we see it all the time in the art world. The majority of Katharina Grosse’s abstract spray paintings on paper and canvas are untitled, or in this case, Ohne Titel or O.T., which means Untitled. However, when choosing not to name a work, it does make sense to assign a separate code or inventory number to each untitled piece to avoid confusion and to give the untitled artworks a name. A good example is John Armleder’s installation titled Untitled, FS 245 from 1990. The work is untitled, yet we still have a specific title to refer to it.

Another great example to give to your titleless works an individual name and to organize them comprehensively within your oeuvre is by adding a series title and number to it—think of the iconic Untitled Film Still series by Cindy Sherman and arguably her most iconic work Untitled Film Still #21 from 1977. As a result, it is safe to say that titles are not a requirement for artists to become successful. However, there is also no doubt that they are an incredible opportunity to play with the meaning and experience of your work. When done right, the title has the power to make elevate the experience of an artwork with just a few words, which brings us to the next chapter.

2. The Power of a Title

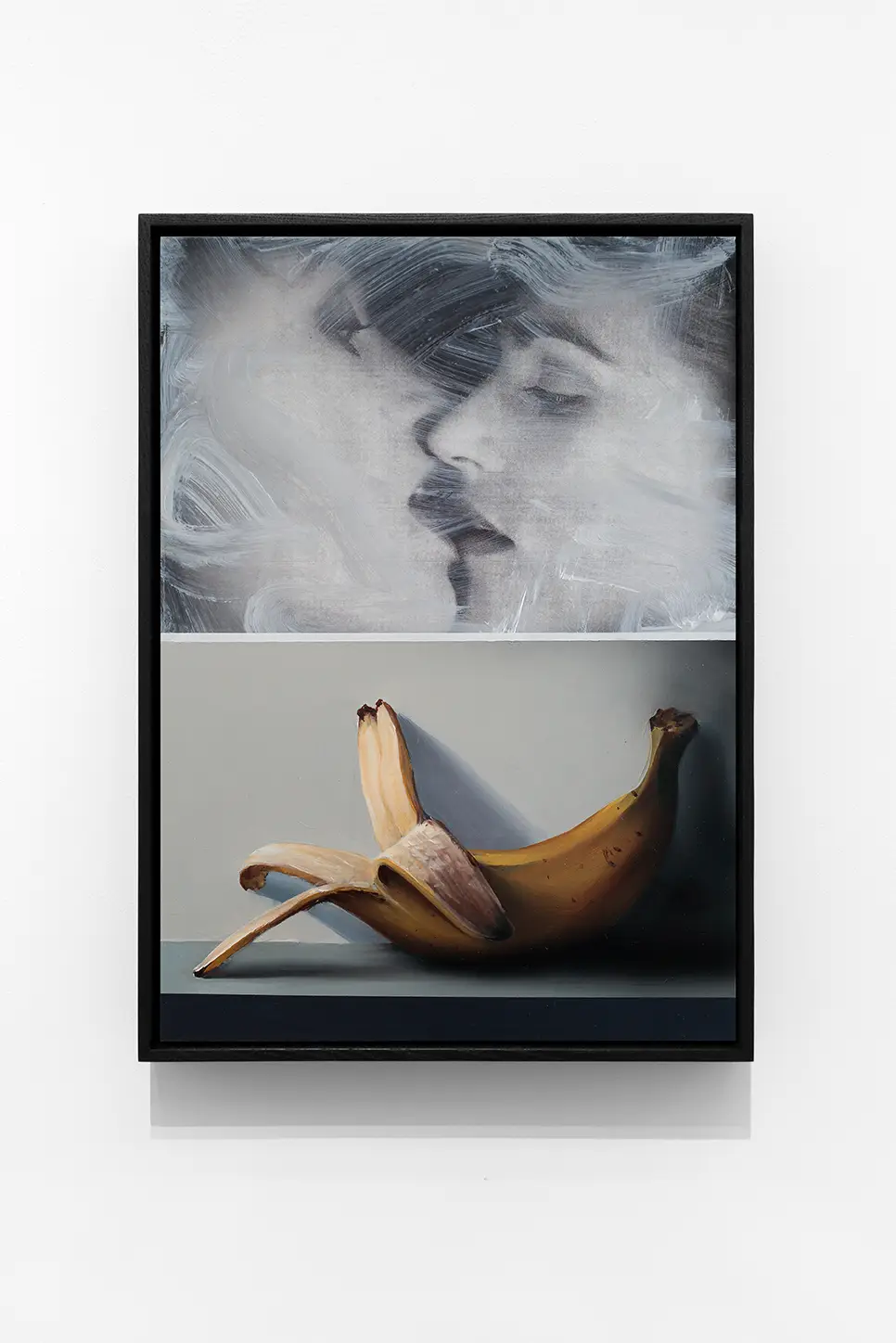

A good title can do many things: create tension, introduce ambiguity, shape a narrative, or offer a subtle guide to interpretation. A poetic or philosophical title may complicate the visual experience, while a humorous or banal one might deflate it—sometimes intentionally. Titles are tools. Use them well, and they can add depth and richness to your work. Sometimes, the artwork makes you think in one particular direction, and then, when reading the title, you move into a completely different direction.

A great example is, for instance, Louise Bourgeois and her iconic, monumental bronze and steel spiders. One might think they are a bit nightmarish or about fear and danger; however, when reading the title Maman, it becomes clear that Bourgeois is hinting at something different. She described the spider as an ode to her mother, who was a tapestry restorer—a profession that involves weaving and repairing, much like a spider’s web. Bourgeois stated, “The spider is an ode to my mother. She was my best friend. Like a spider, my mother was a weaver… Spiders are helpful and protective, just like my mother.” Bourgeois sympathises and admires her mother’s strength.

Yet, it is an ambiguous decision to use specifically these terrifying spiders despite the powerful metaphors and analogies. There must be more to it, and so there is. When being asked why she would fear someone she so clearly adored, the artist responds enigmatically: “I shall never tire of representing her… My reasons belong exclusively to me. The treatment of Fear.” This cryptic remark hints at unresolved tensions characteristic of her oeuvre. Perhaps a sense of betrayal from childhood, such as when Bourgeois’s mother allowed the family’s live-in au pair, who was also her husband’s mistress, to remain in their home for a decade and continue to endure her father’s tyranny. Louise Bourgeois lost her mother when she was 21 years old. Or how a title of just one simple word in combination with a particular image can open up a life of trauma, sorrow, fear, anger, resilience, and solace.1

Or what about Maurizio Cattelan’s Ave Maria (2007), which translates to “Hail Mary,” to title three disembodied, uniformed arms extend from a wall, performing a Roman salute historically associated with authoritarian regimes, including the Roman Empire, Italian fascism, and Nazi Germany. The politically charged gesture confronts themes of mass violence, conformity, and the abuse of power while giving it the title of a prayer. Cattelan repurposes this gesture to critique the historical and political subordination associated with such ideologies and dogmatic thinking in general. A critique that would not be possible if not for its title.

Another great example of the title subtly inciting the reading or possible meaning of an artwork can be found in the multidisciplinary practice of Sophie Nys, who transforms and repositions everyday objects with a sense of humor to uncover the hidden mechanisms of society and the art world—a massive endeavor with just a few minimal interventions, demanding meticulous preparation, wit, and clever titles. For instance, when placing two coconuts in stockings and titling it If Nature Didn’t, Warner’s Will (2012), the artist references and responds to a jolly but sexist 1960s advertisement for Warner’s lingerie. However, the coconuts in stockings look more like a pair of testicles than a pair of breasts, cleverly returning the ad men the favor.

These three examples demonstrate how the title can serve as the principal source of an artwork’s resonance, underscoring both its significance and the conceptual possibilities it unlocks. To unlock this potential, one of the most important mistakes you want to avoid is using titles that spell out precisely what’s happening in the image or artwork. You risk killing the mystery. As illustrated above, great art thrives on ambiguity, multiplicity, and interpretation. So if you paint a landscape with a central figure, let the spectator’s imagination take a stroll with suggestive titles such as Before the Next Light or They Said He Walked Into the Horizon instead of Solitary Figure Facing Forward in a Wide, Open Landscape. A too-literal title can close doors rather than open them. Instead of describing, try evoking. Leave room for viewers to engage with the work on their own terms. Try to creatively play with the fact that the viewer has two reference points of information, the artwork and its title. Instead of being able to connect both points with only one straight line, try to create various possible connections and analogies, meandering from one idea or perspective to another. There is no such thing as one truth or interpretation in postmodern art.

3. Consistency, Codes & Series

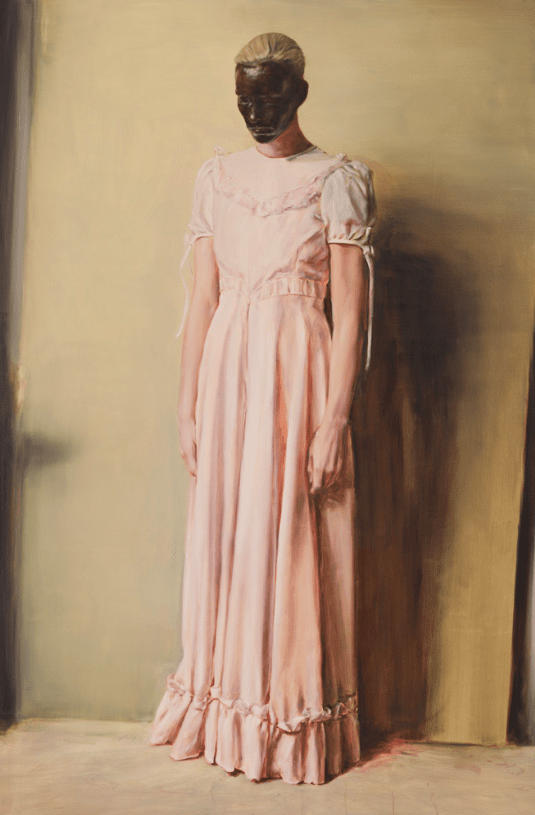

It is also important to note that establishing a consistent way of titling your work can be a valuable part of your artistic voice and can contribute to the overall tone and consistency of your oeuvre. For instance, some artists write long, dramatic titles—think Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) and For the Love of God (2007)—whereas others go for consistent, deceivingly neutral descriptions like Michaël Borremans with titles such as The Pope (2020) or The Angel (2013). Another quite fascinating example is the intuitive or poetic phrases drawn from unconscious associations with the abstract works by Friedric Anderson, for example, using titles like Soaring Prices, Soft-Rock Ballads (2023) or Celestial Convergence, Aubergine Whispers (2023).

Other consistent methods when it comes to titling include using code names, such as Dirk Braeckman and his T.A.-A.N.-96 (1996). His titles offer no clear point of reference, but function as a personal code, indicating the location, with whom, and the year the photograph was taken. While this can be an intentional part of the work’s concept, these titles are hard to remember, hard to refer to, and sometimes difficult for viewers to connect with. More often than not, such pieces are informally renamed by curators or audiences. T.A.-A.N.-96 will most often be referred to as that carpet on the floor of an empty space. Therefore, if you’re using coded titles, make sure it’s a deliberate choice, and consider what you might be missing by not engaging more creatively with the naming process.2

Furthermore, it is possible to use the same title more than once, as it is very common for artists to revisit the same subject more than once. Create a series while using the same title and adding a number to differentiate them. Another common strategy is to pair the artwork title with a reference to a more extensive series. This helps position the work in a broader context while allowing each piece to stand independently. It also signals to viewers and collectors that the work is part of a larger body, which can add conceptual depth and continuity, in which you can see the different connections within the artist’s oeuvre. A great example here is Mircea Suciu with A Beauty Supreme (8) (2018) as the eighth work in which he takes on this concept and in Untitled 15 (Earthly Delights series) (2023) the artwork is untitled but the artist specifies in the title that it is part of his Earthly Delights series.

4. Where Should You Sign or Place the Title on Your Artwork?

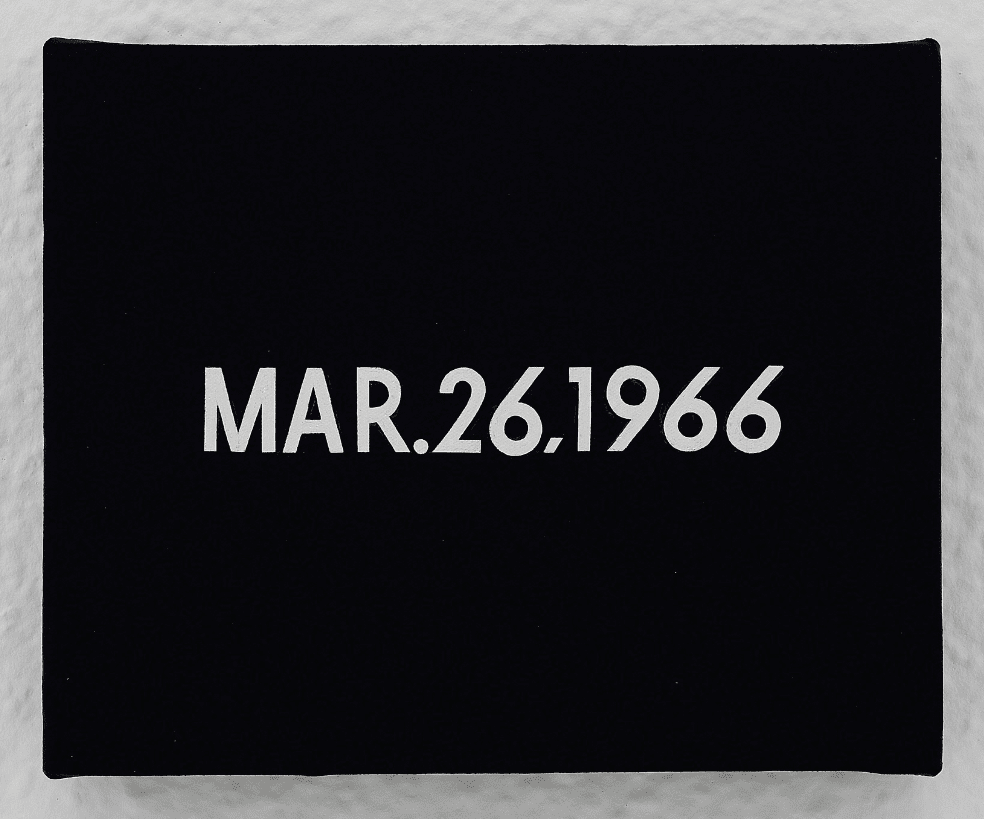

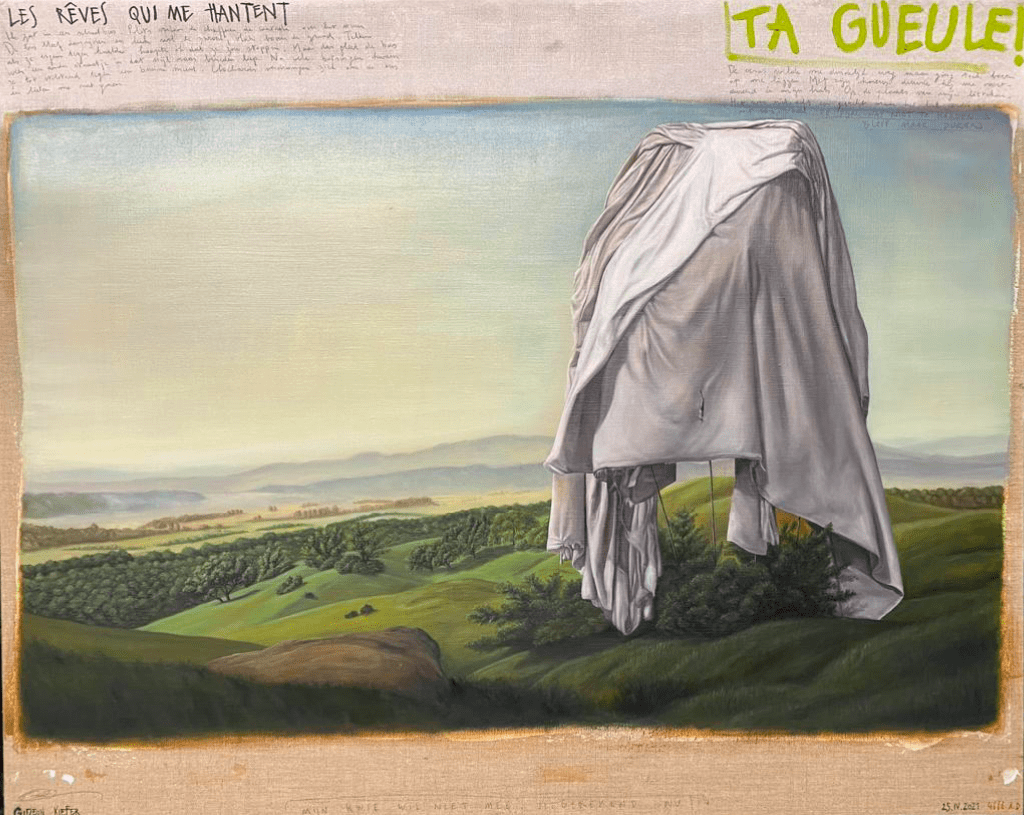

To conclude, where should one be able to find the title of the artwork? First and foremost, on the artwork itself. The most common and professional is on the back of the canvas, panel, or artwork support, or the bottom of a sculpture—in a nutshell, any side that is not facing the viewer. Unless it’s part of the concept, as in some conceptual or text-based works, it’s uncommon to include the title on the front of the piece but it does occassionally happen. Think of On Kawara’s date paintings or Gideon Kiefer’s panels filled with inscriptions and marks that often the title in a very prominent location.

To conclude, you also need to write down the title on the Certificate of Authenticity, as suggested in our COA template and article. And if you no longer have both the artwork and its certificate when it enters the home of a private collector and leads a life of its own—often out of reach of the artist, especially when the sale took place via an art dealer—make sure you have the official title in your personal overview document, inventory, or catalog raisonné to ensure you have documented the official title of the artwork.

For more information about these documents, essential information and career advice for artists in general, make sure to consult our overview page Advice for Artists next.

Cover image: John M. Armleder, Untitled, FS 245, 1990. Acrylic on canvas and Marshall amplifier model 2205 and Marshall box model 1960B — 74 4/5 × 74 4/5 in / 190 × 190 cm. Courtesy Galerie Andrea Caratsch.

Notes:

- Psyche, A Conversation with my spider Maman and Louise Bourgeois consulted April 19, 2025. ↩︎

- M HKA Ensembles, Dirk Braeckman: B.C.-B.X.-01 consulted April 19, 2025. ↩︎

Last Updated on April 19, 2025

About the author:

- Tags: ADVICE FOR ARTISTS, HOME