In November 2024, Sotheby’s New York witnessed one of the most unusual and talked-about art sales of the decade. Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian (2019)—a banana duct-taped to a wall—sold for $5.2 million ($6.24 million with fees) after a swift seven-minute bidding war, making people wonder how we went from Da Vinci to this. So, it is time to look beyond the banana and this Comedian conundrum.

The artwork first gained fame at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2019, where it was presented by Perrotin and quickly became a viral sensation. Selling three editions for $120,000–$150,000 each, Comedian drew attention for its audacious simplicity and humor. Cattelan described it as a “sincere commentary and a reflection on what we value,” a critique of the art market and its mechanisms. It was both derided as a symbol of market excess and praised for its absurd brilliance. As Cattelan remarked, “If I had to be at a fair, I could sell a banana like others sell their paintings. I could play within the system but with my rules.”

Cattelan was born in 1960 in Padua, Italy, and currently resides and works in New York. Over the decades, his oeuvre has ranged from hyper-realistic sculptures to public interventions, often blurring the line between art and prank, but always in the utmost sincere and witty manner. Cattelan spent about a year developing the concept for Comedian, initially experimenting with versions made from bronze and resin—which would arguably align more with his wider artistic practice. However, these attempts felt incomplete. “Everywhere I went, I had this banana on the wall, but I couldn’t figure out how to finalize it,” Cattelan explained in a phone conversation facilitated by Perrotin. “Then, one day, I woke up and realized the banana is meant to be a banana.” And indeed, it is a banana, which became most clear when performance artist David Datuna unpeeled it from the wall and ate it because he “was hungry.”

Despite its hefty price tag, the artwork’s core remains conceptual: a banana, meant to be replaced periodically, taped to a wall. The banana is a quintessential example of his conceptual approach: deceptively simple and humorously subversive. Cattelan intentionally left its meaning open-ended, though the piece has been interpreted as a commentary on consumerism, fleeting materialism, and the art market’s self-parody. As Comedian went viral and sparked global controversy, it arguably became Cattelan’s most iconic work in recent years, and Cattelan is one of the most important artists of his generation—hence the price.

However, Cattelan does not provoke for the sake of provocation. Instead, he wants to hold up a mirror to society. The artist says, “I actually think that reality is far more provocative than my art (…) I just take it; I’m always borrowing pieces—crumbs really—of everyday reality. If you think my work is provocative, it means that reality is extremely provocative, and we just don’t react to it. Maybe we no longer pay attention to the way we live in the world.” Cattelan does not aim to shock you with his banana but uses the everyday with his ready-made sculpture to question the everyday and the very principles leading up to the controversy, elevating the value of his work, art, and things in general, he is questioning in the first place.

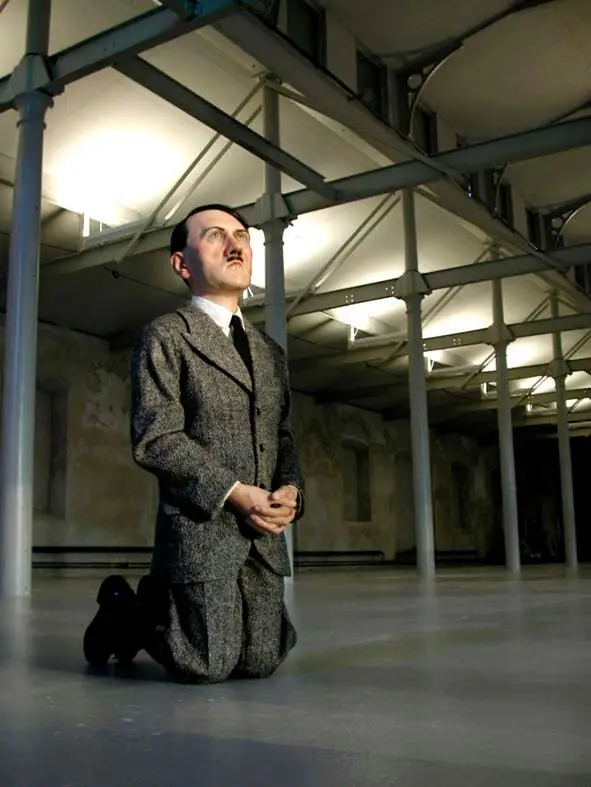

Although the banana is very telling for Cattelan’s conceptual approach, it is not entirely representative of the rest of his oeuvre, nor is it his most expensive artwork. In 2000, at Christie’s in New York, the iconic artwork Him (2000) was sold for over $17 million. The artwork is a wax figure of Hitler, kneeling and seemingly praying, in the typical mini format of Cattelan’s self-portraits. A controversial work of art once more led to a mind-boggling price—but the price tag was never the goal but only an effect. The image of Hitler is a troubling one, yet it exists in popular imagination. Cattelan aims to face this dark shadow cast upon our history, identity, and its tangible presence throughout post-war art.

Cattelan states, “I wanted to destroy it myself. I changed my mind a thousand times, every day. Hitler is pure fear; it’s an image of terrible pain. It even hurts to pronounce his name. And yet that name has conquered my memory, it lives in my head, even if it remains taboo. Hitler is everywhere, haunting the specter of history; and yet he is unmentionable, irreproducible, wrapped in a blanket of silence.” The work evokes unease but also moral introspection. It might spark controversy, but it also demands engagement, challenging viewers to confront complex cultural and historical narratives—a continuum throughout his practice functioning as the foundation for the art world’s appreciation for his work, which one cannot ignore nor forget.

Another controversial and iconic artwork by Cattelan was created a year prior to Him. It is a wax sculpture of Pope John Paul II lying on the ground after being struck by a meteorite titled La Nona Ora (1999), which translates to the Ninth Hour. The title refers to the moment Christ cried, “Why have You forsaken me?” before dying on the cross. Suffering, absurdity, science-fiction, humor, and a deliberate open-ended as Cattelan refuses to give it a straightforward meaning as for Cattelan, the duty is to ask questions instead. It successfully evokes numerous readings, interpretations, and reflections. Some see the resilience of the cross, which is still intact after being hit by a meteor, and others read it as a comment on the scandals of the Catholic Church. As with Comedian, Cattelan does not remain vague about the meaning of his works because it is all smoke and mirrors; he does so to ignite a conversation, and not end one.

In Ave Maria (2007), which translates to “Hail Mary,” three disembodied, uniformed arms extend from a wall, performing a Roman salute historically associated with authoritarian regimes, including the Roman Empire, Italian fascism, and Nazi Germany. The imagery references Jacques-Louis David’s The Oath of the Horatii (1784), a neoclassical painting depicting three brothers pledging loyalty to their nation, visually represented by raised arms. The politically charged gesture confronts themes of mass violence, conformity, and the abuse of power while giving it the title of a prayer. Cattelan repurposes this gesture to critique the historical and political subordination associated with such ideologies and dogmatic thinking in general, presenting various layers of meaning beyond the controversy.

Comedian might not have the same weight and sculptural qualities as the three artworks mentioned above, but when knowing Cattelan’s work, one approaches the banana differently, and the conversation begins. The price tag does not help either; it never does. It spoils the fun, pollutes your judgment, and, in the end, has nothing to do with art or the intention of the artist. Perhaps that is exactly what the artwork says. One has to look at art for what it is, free from monetary associations and the mechanisms of the art market—if we still can. Only the sheer banality of a banana—and not a bronze sculpture of a banana—was able to do so, to see art for what it actually is, contributing to Cattalan’s ingenious and characteristic rejection of the institutionalization and mystification of art.

Last Updated on April 15, 2025

About the author:

- Tags: HOME